On January 19, 1936, British archaeologist Walter Bryan Emery made a fascinating discovery while excavating the Saqqara necropolis in Egypt. This find took place in mastaba S3111, the tomb of an esteemed Egyptian official named Sabu, who lived during the First Dynasty, around 3000-2800 BC. The unearthed artifact, now famously known as the Sabu Disk, continues to puzzle historians and archaeologists to this day due to its unique design and unclear function.

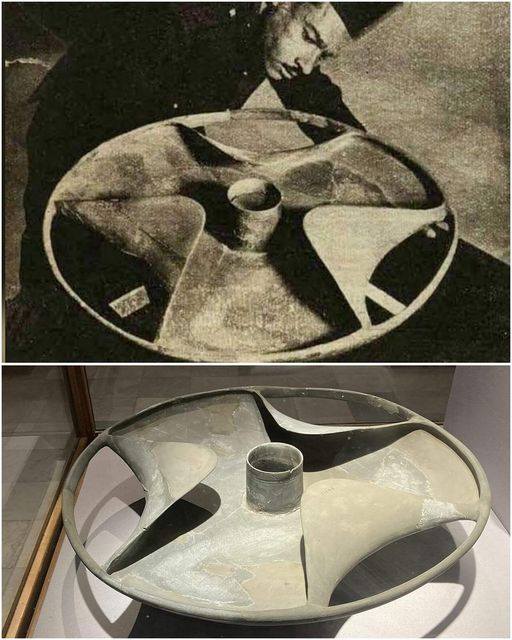

The Sabu Disk is a concave slate disc with a diameter of 61 centimeters and a maximum height of 10.6 centimeters. At its center, there is an 8-centimeter-wide hole, and from the outer edge, three distinct lobes or “wings” extend, giving it a shape reminiscent of a steering wheel with three broad spokes. This unusual structure sets it apart from any other known artifacts of ancient Egypt, leading to a wide array of theories about its purpose.

When Emery discovered the artifact, it was fragmented within Sabu’s burial chamber, alongside the official’s skeletal remains. After painstakingly restoring it, he placed the disk in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, where it remains on display today. The artifact stands out as the only known example of its kind in ancient Egyptian history, further deepening the mystery surrounding its purpose.

The First Dynasty was a period of great innovation in craftsmanship, as evidenced by the production of large, high-quality stone bowls, plates, and intricately carved slate objects. Yet, none resemble the Sabu Disk, suggesting it was not a commonplace item but rather something of great significance, possibly crafted exclusively for Sabu. This could indicate his high status in ancient Egyptian society, marking him as an individual of importance.

Despite extensive research, the function of the Sabu Disk remains uncertain. Emery speculated that it might have served as a type of container mounted on a support, although no evidence of such a structure was found. Other scholars have suggested that it could be an imitation of contemporary metal objects. Given its delicate structure, some believe it may not have been used for practical purposes at all, instead serving a decorative or ceremonial function.

More speculative theories propose that the disk functioned as a triple-flame oil lamp or even as a flywheel meant to store rotational energy. In modern times, engineers from Airbus analyzed 3D replicas of the artifact and noted that its design exhibits aerodynamic properties, suggesting it could have functioned as a sophisticated throwing implement. However, the disk’s radial symmetry rules out its use as a propeller or turbine, despite claims made by supporters of pseudoscientific interpretations.

One potential clue to its origins comes from an artifact dating back to the Nagada II period, a phase of the Egyptian predynastic era that spanned from roughly 3500 to 3400 BC. Housed in the Petrie Museum in London, this object is a clay figurine featuring a round disk decorated with four snakes. Three of the snakes are depicted with their heads raised, forming a circular pattern around a central round container, while the fourth appears to be drinking from it. Some researchers have drawn parallels between this figurine and the Sabu Disk, theorizing that the disk may have held a symbolic or religious function.

Sabu himself was likely an administrator or governor of a city or province, serving under the reigns of Pharaohs Den and Anedjib. Some scholars speculate he may have even been the son of Anedjib. When archaeologists uncovered his tomb, they found his remains still inside a wooden sarcophagus, positioned on its side in accordance with burial customs of the time. Inside the funerary chamber, various belongings of Sabu were preserved, including stone tableware, metallic elements, and the enigmatic disk.

The Sabu Disk, despite its elusive purpose, holds great historical value for multiple reasons. It serves as a remarkable testament to the advanced stone craftsmanship of late predynastic Egypt and the First Dynasty. The artifact showcases the skill and ingenuity of ancient Egyptian artisans, who demonstrated their mastery of stonework long before the construction of the great pyramids.

The significance of this discovery extends beyond its craftsmanship. The disk raises important questions about the technological capabilities and artistic expressions of early dynastic Egypt. If it was indeed a functional object, its use remains unknown—whether as a tool, a component of a larger mechanism, or a ritual item. If purely ornamental, its intricate design suggests a deeper cultural or religious meaning that has yet to be fully understood.

The lack of similar artifacts only deepens the intrigue. Unlike the countless bowls, plates, and ceremonial objects that have been unearthed from this period, the Sabu Disk stands alone in its uniqueness. Some scholars speculate that it may have been a highly specialized object, possibly representing a now-lost category of items that played a significant role in early Egyptian society.

As with many archaeological mysteries, new interpretations continue to emerge. Theories surrounding the Sabu Disk range from the plausible to the extraordinary, with some even venturing into the realm of science fiction. While there is no evidence to suggest extraterrestrial involvement, as some fringe theorists claim, the artifact does highlight the ingenuity of early civilizations and their ability to create objects of both aesthetic and functional value.

Ultimately, the Sabu Disk remains one of the most puzzling and captivating finds from ancient Egypt. Whether it was a practical tool, a ritual object, or simply a masterful work of art, its significance endures. The artifact serves as a reminder of how much we still have to learn about early Egyptian civilization, inspiring archaeologists and historians to continue exploring the rich and complex history of one of the world’s greatest ancient cultures.