The Abu Simbel Temple is a monumental rock-cut temple complex situated on the border between Egypt and Sudan. Constructed during the reign of the powerful Pharaoh Ramesses II in the 13th century BC, the complex consists of two temples that were originally carved into the mountainside. Although it is widely known today as the Abu Simbel Temple, it was historically referred to as the “Temple of Ramesses, Beloved by Amun.” In the 1960s, the construction of the Aswan High Dam and the creation of Lake Nasser threatened the temple’s existence, leading to its complete relocation in 1968.

The temple complex features two grand structures—the Great Temple and the Small Temple—both of which exemplify ancient Egyptian architectural and artistic achievements. Commissioned by Ramesses II, one of Egypt’s most renowned pharaohs, the construction of the Abu Simbel Temple began around 1264 BC, according to some scholars. This estimate is based on the artwork within the Great Temple, which commemorates Ramesses II’s victory over the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC. Another theory suggests that construction began in 1244 BC, following Ramesses II’s military campaigns against the Nubians, as the temple is strategically located on the border with Nubia. Regardless of the exact start date, it is widely agreed that the construction of the temple took approximately 20 years to complete.

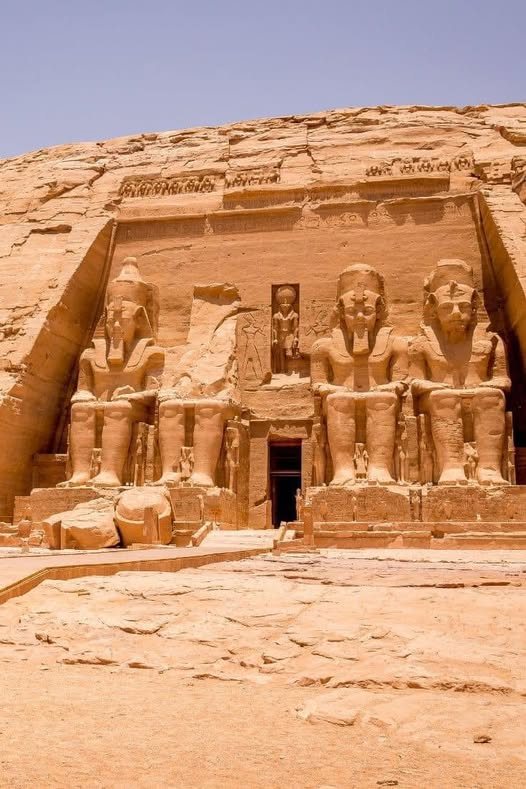

The entrance of the Great Temple is adorned with four colossal seated statues of Ramesses II, each standing an impressive 20 meters (65 feet) tall, gazing out over all who approach the monument. The Small Temple, believed to have been dedicated to Nefertari, the beloved wife of Ramesses II, features an entrance guarded by six statues—two of Nefertari and four of the pharaoh—each measuring 10 meters (33 feet) in height. The sheer scale and craftsmanship of these statues reflect the pharaoh’s desire to demonstrate his power and divine connection to both his subjects and the gods.

One of the most remarkable features of the Great Temple is its inner sanctum, which houses four statues representing the deities Ra, Amun, and Ptah, along with a statue of Ramesses II himself. The temple’s design is such that twice a year, on February 21st and October 22nd, the Sun’s rays penetrate the temple’s inner chambers, illuminating three of the four statues—Ra, Amun, and Ramesses—while the statue of Ptah remains shrouded in darkness, likely due to his association with the Underworld. These dates are traditionally believed to coincide with the pharaoh’s birthday and coronation, although no definitive evidence supports this theory. Nonetheless, the alignment of the temple with the Sun underscores the ancient Egyptians’ advanced understanding of astronomy and their desire to harmonize their religious practices with celestial events.

Over time, the Abu Simbel Temple fell into disuse and was gradually buried under layers of desert sand, remaining hidden for centuries. The monument was rediscovered in the early 19th century, with Swiss traveler and geographer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt often credited for its rediscovery. According to one version of the story, Burckhardt spotted the partially exposed top of the Great Temple while traveling along the Nile River in 1813. Another version suggests that an Egyptian boy named Abu Simbel led Burckhardt to the site, which was subsequently named after the boy. Unable to excavate the temple himself, Burckhardt shared his discovery with his friend, Giovanni Battista Belzoni, who attempted to unearth the temple but was initially unsuccessful. In 1817, Belzoni returned to the site, successfully excavated the temple, and removed numerous artifacts and valuable items from its chambers.

In the 1960s, the construction of the Aswan High Dam posed a new threat to the Abu Simbel Temple. The dam’s construction would create Lake Nasser, a massive reservoir that would submerge the temple complex underwater. Recognizing the cultural and historical significance of the site, an international campaign was launched to save the temple. After considering various proposals, the decision was made to dismantle the temple and reconstruct it on higher ground. This monumental task began in 1964 and required the expertise of engineers, archaeologists, and laborers from around the world. The process involved cutting the two temples into 1,035 blocks, each weighing between 20 and 30 tons. The colossal seated statues of Ramesses II, along with six standing statues of the pharaoh, were also sawn into sections. These massive stone blocks and statues were then carefully hoisted to the top of a cliff, 64 meters (210 feet) above their original location, where they were meticulously reassembled to replicate the original layout of the temples. To preserve the site’s aesthetic harmony and protect it from potential flooding, artificial hills were constructed around the temples, creating a natural-looking barrier against the waters of Lake Nasser.

The relocation of the Abu Simbel Temple is regarded as one of the greatest feats of archaeological engineering in modern history. The success of this international endeavor not only preserved an invaluable piece of ancient Egyptian heritage but also demonstrated the importance of global cooperation in protecting cultural landmarks. Today, the temple complex is part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the “Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae” and remains one of Egypt’s most popular tourist destinations, second only to the Pyramids of Giza. Visitors from around the world continue to marvel at the temple’s grandeur, the ingenuity of its ancient builders, and the modern engineering marvel that saved it from destruction, ensuring that future generations can appreciate this extraordinary testament to human creativity and perseverance.