Archaeologists from the University of Cambridge and Liverpool John Moores University have successfully reconstructed the face of a Neanderthal woman who lived approximately 75,000 years ago. This remarkable achievement challenges long-standing perceptions of what our ancient relatives may have looked like and offers fresh insights into their level of sophistication and their similarities to modern humans.

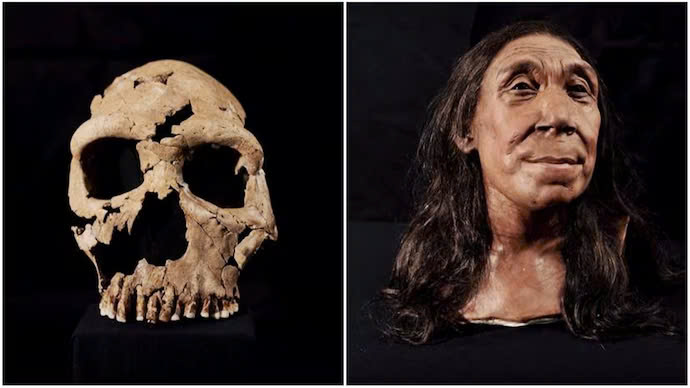

The Neanderthal woman, identified as Shanidar Z, was discovered in the Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan in 2018. Her skull, however, was found in a highly fragmented state, having been crushed into nearly 200 pieces—likely the result of a rockfall that occurred shortly after her death. The damage made her facial reconstruction an intricate and painstaking process, requiring advanced archaeological and scientific techniques to piece together her features accurately.

Dr. Emma Pomeroy, a paleoanthropologist from the University of Cambridge, described the endeavor as akin to solving an exceptionally complex three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. The researchers needed to carefully extract each tiny fragment from the sediment while ensuring the delicate remains were not further damaged. Once the individual fragments were identified and stabilized, they were reinforced with a specialized glue-like consolidant to preserve their structure. The team then wrapped each piece in foil and transported them for further study and meticulous reassembly.

With the skull reconstructed, the next step was to bring Shanidar Z’s face back to life. Acclaimed paleoartists Adrie and Alfons Kennis, renowned for their lifelike depictions of early humans, used the reconstructed skull as a foundation for a detailed facial reconstruction. Their expertise allowed them to create an accurate representation of what Shanidar Z may have looked like when she was alive, offering the public an unprecedented glimpse into the past.

One of the most striking revelations from this reconstruction is that Neanderthals may have been more similar to modern humans than previously assumed. While it has long been accepted that Neanderthals possessed distinctive skeletal features—including prominent brow ridges, a wider nasal cavity, and the absence of a chin—the reconstructed face of Shanidar Z suggests that these differences may not have been as pronounced in life as fossilized remains tend to indicate. Her features appear softer, and her expression conveys a level of humanity that challenges outdated depictions of Neanderthals as primitive or brutish.

Beyond aesthetics, the implications of this discovery extend into the realm of genetics and human evolution. The reconstruction of Shanidar Z’s face adds another layer of complexity to the discussion about the interactions between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. Genetic research has already established that modern humans carry Neanderthal DNA, with most non-African populations possessing small but significant traces of their genetic heritage. This suggests that interbreeding between the two species was not only possible but likely occurred over an extended period.

Dr. Pomeroy emphasized the significance of this by stating, “Almost everyone alive today still has Neanderthal DNA, which tells us that the relationship between our species was much closer than many had once believed.” The presence of Neanderthal genetic markers in modern populations reinforces the idea that these ancient humans were not an entirely separate species but rather close relatives who coexisted and, in some cases, intermingled with early Homo sapiens. This challenges the long-held notion that Neanderthals were an evolutionary dead end, instead positioning them as an integral part of the human story.

The unveiling of Shanidar Z’s face is not merely an academic achievement; it is a profound moment that allows us to connect with our ancient past on a deeply human level. By seeing her reconstructed features, we gain a better understanding of who the Neanderthals were—not just as a species, but as individuals with lives, experiences, and complexities comparable to our own. This realization invites us to reconsider how we view human evolution and the factors that shaped the development of modern humanity.

The importance of this discovery extends beyond anthropology and archaeology. The ability to reconstruct ancient faces using advanced scientific methods highlights the progress that has been made in the field of paleoanthropology. From sophisticated imaging techniques to forensic facial reconstruction, researchers now have more tools than ever to breathe life into the past. These advancements enable us to create visual representations of our ancestors that are more accurate and scientifically grounded than ever before.

The reconstruction of Shanidar Z’s face has also gained widespread public attention, in part due to its feature in the Netflix documentary Secrets of the Neanderthals. This documentary provides a closer look at the detailed process behind the reconstruction, as well as the broader implications of the discovery. Through the power of visual storytelling, it brings the world of the Neanderthals into sharp focus, making it accessible to audiences who may not have otherwise engaged with paleoanthropology.

The documentary, along with the research itself, underscores the growing interest in understanding early human history and the evolutionary journey that led to modern Homo sapiens. By reconstructing faces from the past, scientists bridge the gap between ancient history and contemporary audiences, offering a tangible connection to the individuals who once roamed the earth tens of thousands of years ago.

Shanidar Z’s story is particularly significant because the Shanidar Cave has long been associated with remarkable Neanderthal discoveries. Previous finds at the site have suggested that Neanderthals practiced some form of ritual burial, an indication of cultural and cognitive complexity. The presence of pollen grains near some Neanderthal remains in the cave has even led to speculation that they may have placed flowers around their dead, an act that—if confirmed—would further challenge outdated notions of Neanderthals as lacking emotional depth.

The reconstruction of Shanidar Z adds yet another layer to this evolving narrative. Her face is not just a scientific reconstruction; it is a window into a lost world, a representation of an individual who lived, breathed, and experienced life in ways that may not have been so different from our own. It serves as a reminder that history is not just about dates and artifacts—it is about people, and each discovery brings us closer to understanding those who came before us.

Ultimately, this groundbreaking reconstruction is a testament to the advancements in scientific research, the dedication of archaeologists, and the power of collaboration across disciplines. It reinforces the idea that history is not static but continually evolving as new discoveries reshape our understanding of the past. As we learn more about Shanidar Z and her Neanderthal relatives, we move closer to unraveling the intricate web of human evolution, shedding light on the complex relationships that shaped who we are today.

Shanidar Z’s reconstructed face stands as a powerful symbol of connection—between past and present, science and humanity, and the ever-growing knowledge of where we come from. With each new discovery, the story of our ancient ancestors becomes richer and more nuanced, reminding us that the past is not so distant after all.