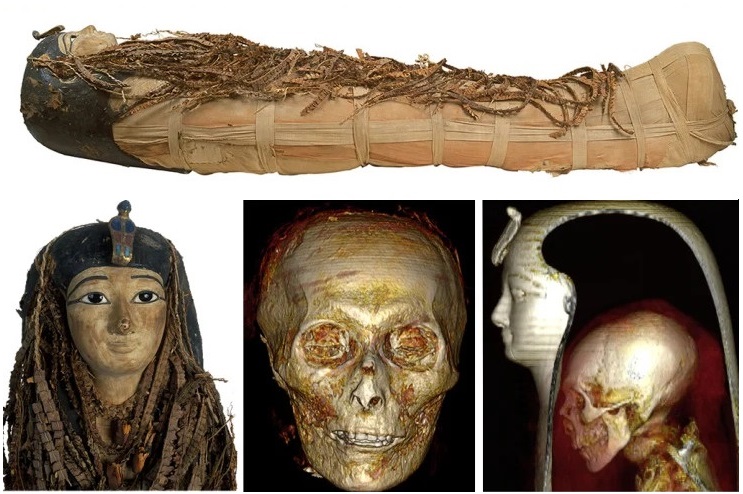

For over three thousand years, the mummy of Amenhotep I, one of ancient Egypt’s most celebrated pharaohs, remained untouched. Reverently wrapped in linen, adorned with delicate flower garlands, and shielded by a finely crafted face mask that preserved his royal features, his body was a symbol of reverence and mystery. Unlike other royal mummies that were unwrapped and studied in past centuries, Amenhotep I was spared such treatment. Scientists long resisted physically disturbing the carefully preserved remains, fearing the irreversible damage that might occur. However, thanks to advancements in modern technology, a team of Egyptian researchers recently employed high-resolution CT scans to digitally “unwrap” the mummy, offering a rare and detailed glimpse into the life, death, and burial rituals of this ancient ruler—without unsealing a single layer of linen.

The digital analysis brought to light a wealth of information about the pharaoh’s physical attributes, health, and the care that went into his burial and later restoration. Amenhotep I ruled Egypt during the 18th Dynasty, specifically from around 1525 B.C. to 1504 B.C., and his reign is remembered for its stability, monumental construction projects, and strong religious devotion. The scan revealed that at the time of his death, Amenhotep I was approximately 35 years old and stood around 5 feet 5 inches tall (169 centimeters). Remarkably, he had excellent teeth, showing no signs of dental disease—a significant detail considering the often poor dental conditions of many ancient Egyptians. The scans also showed that he was circumcised, a detail that aligns with royal customs and religious practices of that era.

One of the most intriguing discoveries beneath the linen wrappings was the presence of 30 amulets placed throughout his body. These amulets were strategically positioned, likely intended to offer protection and magic in the afterlife. In addition to these, the researchers discovered an ornate golden girdle decorated with beads. This ceremonial item was believed to possess mystical significance, potentially playing a role in securing a safe journey to the afterlife or symbolizing divine favor. The presence of such elaborate burial items illustrates the immense spiritual and cultural importance placed on the afterlife by the ancient Egyptians and reaffirms Amenhotep I’s high status.

Although Amenhotep I’s body had remained sealed for thousands of years, the scans revealed that he had not escaped the ravages of time—or the hands of ancient tomb robbers. His body bore signs of trauma, including a fractured neck, decapitation, and dismembered limbs, damage consistent with looting. Tomb raiders, often in search of gold or other valuables, frequently caused such destruction. However, what truly moved researchers was the evidence of restoration carried out by priests during Egypt’s 21st Dynasty—several centuries after the pharaoh’s death. These priests, likely motivated by both spiritual duty and a desire to preserve royal dignity, took great care to repair the damage. They reattached the head and limbs using resin, a common adhesive in ancient embalming, and rewrapped the entire body in fresh linen, effectively restoring the mummy to a dignified state.

These acts of reverence by the 21st Dynasty priests underscore the profound respect ancient Egyptians had for their deceased kings. Far from simply burying the pharaoh once and forgetting him, later generations actively maintained the sacred integrity of royal mummies, especially those of revered figures like Amenhotep I. This care reflects the cultural and religious importance of the afterlife in Egyptian society, where a pharaoh’s legacy and spiritual wellbeing were believed to impact the health of the entire kingdom.

Beyond physical preservation, the CT scans also allowed researchers to reconstruct the face of Amenhotep I, giving modern audiences an impression of what the pharaoh may have looked like in life. Based on the digital imaging, Amenhotep I had a narrow chin, a small and slim nose, slightly protruding upper teeth, and curly hair. These features bore a striking resemblance to those of his father, Ahmose I, suggesting a strong familial likeness. It is rare in the field of Egyptology to encounter such detailed visual reconstructions of ancient rulers without physical interference, making this discovery all the more valuable.

For Egyptologists, Amenhotep I’s mummy has always stood apart. It was one of the few royal mummies that had never been unwrapped or extensively studied, largely due to its remarkably pristine condition. The use of non-invasive digital technology enabled scholars to explore the intricacies of ancient embalming and burial rituals without compromising the physical integrity of the mummy. More importantly, it offered unprecedented insight into how royal mummies were treated long after their initial burial, shining a spotlight on the priesthood of the 21st Dynasty and their role in preserving Egypt’s sacred history.

While not all scholars agree on the broader implications of these findings, the project’s results are widely viewed as a landmark moment in modern archaeology. The successful digital unwrapping not only preserved Amenhotep I’s remains but also elevated our understanding of the values and beliefs that shaped one of the world’s oldest civilizations. The team’s work demonstrates how ancient customs and modern science can intersect in powerful ways, unlocking knowledge once thought forever sealed behind linen and time.

In the end, Amenhotep I’s mummy is more than a preserved body—it is a window into the spiritual and political soul of ancient Egypt. Through careful study, the digital revelations offer us more than just data—they reconnect us to the humanity, reverence, and deep cultural traditions that defined an entire civilization. For modern readers and researchers alike, these insights breathe new life into the distant past, making the story of Amenhotep I not just a tale of ancient royalty, but a testament to the enduring legacy of Egyptian civilization.