Old London Bridge was far more than a simple crossing over the River Thames—it stood as a vibrant, living embodiment of medieval ingenuity, a remarkable structure that shaped the very fabric of London for over 600 years. Built in 1176 under the guidance of Peter of Colechurch, often known as Peter the Bridge Master, the bridge wasn’t just a passage from one riverbank to another. It was a thriving microcosm of urban life suspended above the flowing waters, an architectural marvel that reflected both the ambitions and capabilities of 12th-century England.

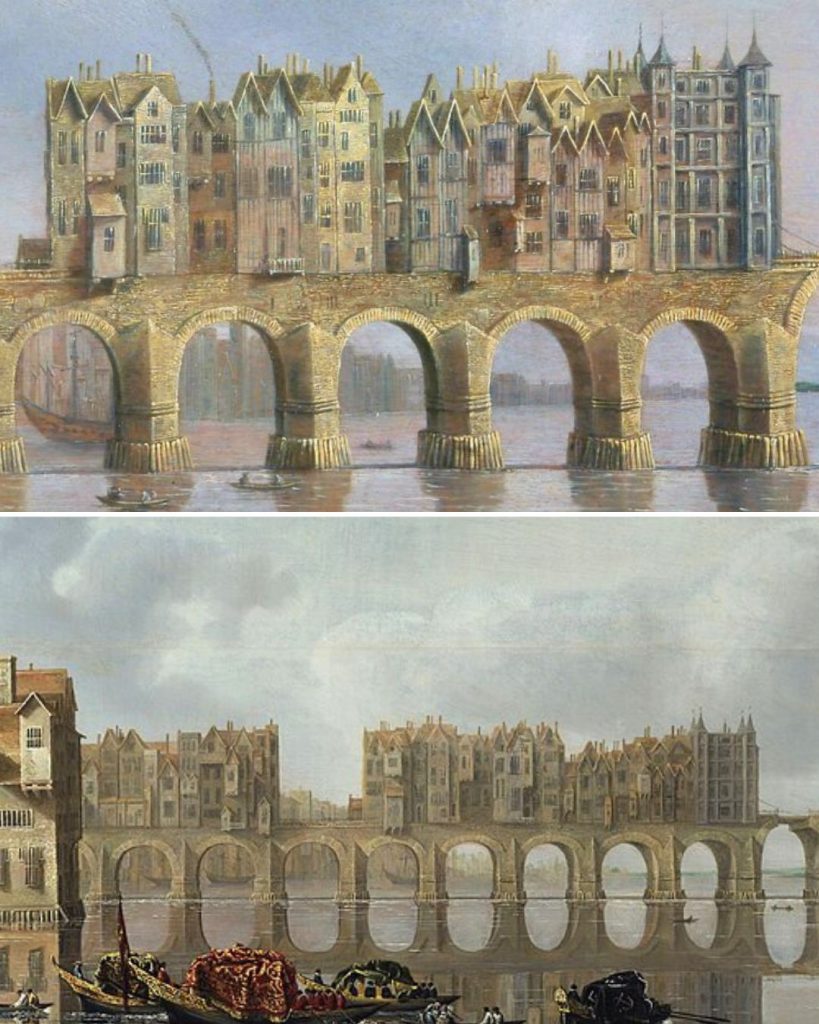

The bridge stretched an impressive 926 feet, supported by 19 carefully constructed pointed stone arches. Its foundation was a triumph of medieval engineering—massive wooden stakes were driven deep into the riverbed and packed tightly with rubble, creating a stable platform for the enormous weight it would bear. But the Old London Bridge was more than just structurally sound; it was astonishingly unique in its design. From its inception, it was lined with buildings—homes, shops, and even places of worship. This mix of function and community set it apart from other bridges of its time, making it not just a feat of construction but a testament to medieval urban planning.

At the height of its occupancy in the 14th century, around 140 buildings were crowded along the bridge, some soaring four or five stories high. These weren’t just any homes or businesses—they were occupied by highly regarded tradespeople, including haberdashers, glovers, cutlers, and fletchers who crafted arrows for warfare and sport. The bustling environment created a marketplace in mid-air, where merchants shouted their wares, residents leaned from their windows, and children played above the rushing waters. Life on the bridge was vivid, noisy, and constantly moving. Yet the bridge served more than just economic or residential needs. It was a strategic military point, outfitted with a drawbridge that could be raised in times of attack, protecting the city from invaders who might approach by water.

Among the bridge’s most iconic features were three prominent structures that told the story of London’s turbulent religious and political shifts. The first was a chapel dedicated to St. Thomas Becket, constructed at the center of the bridge as both a place of worship and a place for travelers to rest and pray. After the English Reformation in the 16th century, the chapel was deconsecrated and repurposed as a residential dwelling, mirroring the broader transformation of religious life in England. The second was the drawbridge tower, a functional yet symbolic structure that played a key role in London’s defenses. And the third, perhaps the most notorious, was the stone gate at the Southwark end of the bridge. It became infamous as the place where the severed heads of executed traitors were gruesomely displayed on spikes—grim warnings to those who might dare challenge the monarchy.

Despite its heavy use and exposure to disasters, Old London Bridge proved astonishingly resilient. Most famously, it survived the Great Fire of London in 1666, an inferno that obliterated 13,200 homes and 87 parish churches across the city. The bridge’s survival can be partly attributed to a smaller fire that had broken out earlier and cleared several buildings, effectively creating a firebreak that stopped the larger blaze from spreading across the entire structure. This twist of fate preserved the bridge for future generations.

However, as the centuries passed, the once-glorious bridge began to show its age. By the early 1700s, it was becoming more of a hindrance than a help. Its narrow arches obstructed the natural flow of the Thames, making navigation difficult for ships. In cold winters, the limited space between the piers contributed to ice buildup, leading to frequent and dangerous freezes. Pedestrians and vehicles alike struggled to cross its worn and uneven surface. Recognizing the need for modernization, construction began on a new bridge in 1824. The replacement was completed and opened to the public in 1831, signaling the end of an era.

Despite being dismantled, the spirit and story of Old London Bridge endured. It captivated artists and writers for generations. Dutch painter Claude de Jongh captured its image in 1630, portraying the bridge’s bustling life and architectural details with stunning clarity. British artist J.M.W. Turner followed in 1794 with his own interpretation, embedding the bridge into the artistic heritage of Britain. These visual records serve as timeless reminders of what the bridge once was—a bustling, beautiful artery of old London.

Today, a modern bridge stands in the same place, functional and clean-lined, lacking the charm and chaos of its predecessor. It is owned and maintained by the Bridge House Estates, a charitable trust overseen by the City of London Corporation. Though it serves a more straightforward purpose now, its presence is still a tribute to the layers of history that once played out over the Thames.

A few fascinating details highlight just how extraordinary the original bridge really was. In 1896, when the replacement bridge was at its busiest, nearly 8,000 pedestrians and 900 vehicles crossed it every single hour. At one point, the structure was sinking—so much so that the eastern end of the bridge sat three to four inches lower than the western side. And in more recent memory, the current bridge was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II on March 16, 1973, marking a new chapter in a centuries-long story.

Old London Bridge is far more than a lost piece of infrastructure. It stands as a symbol of London’s creativity, determination, and ability to evolve. It was an emblem of resilience in times of danger, a beacon of innovation in an age without modern tools, and a foundation on which the city’s vibrant identity was built. Though the original stones are gone, its legacy remains etched in the heart of the city and in the stories still told about the bridge that once held a whole world above the water.