In 1965, a Ukrainian farmer from the quiet village of Mezherich began a simple task: he wanted to expand his basement. What he didn’t realize was that his everyday project would soon lead to one of the most astonishing archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. As he dug deeper, his shovel struck something solid. Brushing the dirt away, he uncovered a massive jawbone. At first glance, it may have seemed like just another old fossil, but it was, in fact, the jaw of a woolly mammoth—just the beginning of a find that would captivate the archaeological world for decades to come.

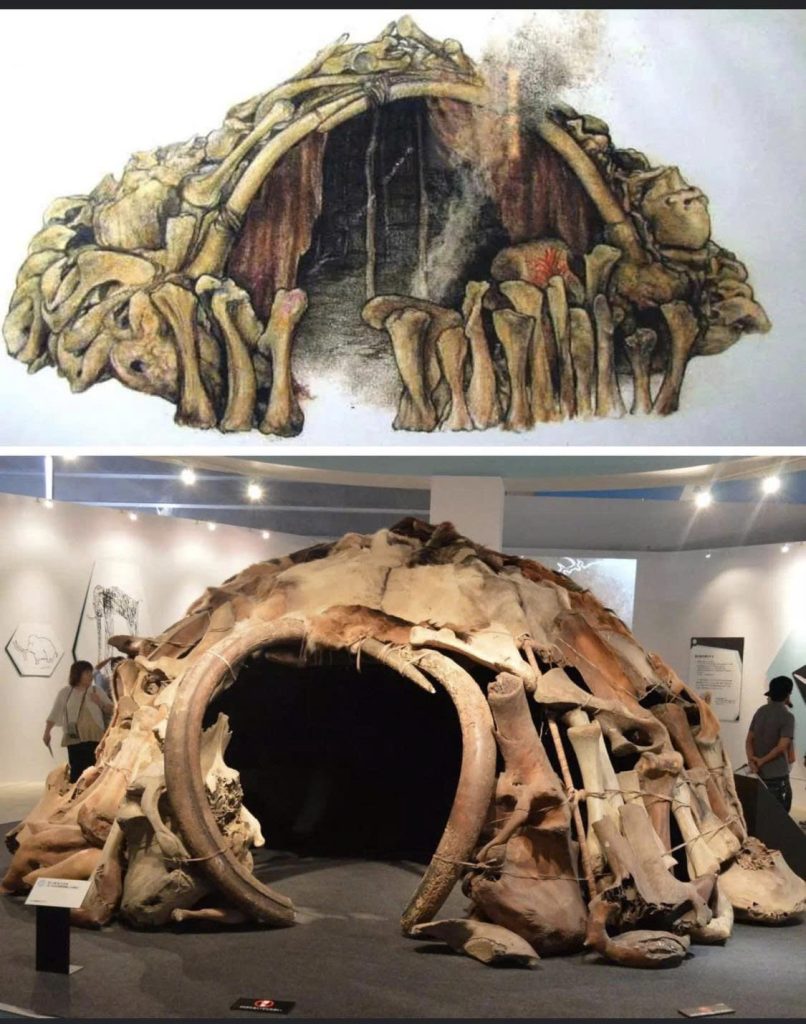

What followed was anything but ordinary. As more bones surfaced, the scale of the discovery quickly became evident. Professional archaeologists were brought in to investigate, and what they uncovered was nothing short of extraordinary. Hidden beneath the soil were the remains of four prehistoric huts, ingeniously constructed using 149 mammoth bones. These weren’t just piles of ancient bones—they were deliberate, expertly crafted shelters, offering an unprecedented glimpse into Ice Age life.

These mammoth bone huts, estimated to be around 15,000 years old, are remarkable for many reasons. Chief among them is what they reveal about the adaptability and resourcefulness of early humans. At a time when timber was scarce—especially on the tundra, where trees were few and far between—these ancient people turned to what was readily available in their environment: the bones of the woolly mammoth. Far from being crude constructions, these shelters demonstrate advanced planning, craftsmanship, and a deep understanding of survival in extreme conditions.

The architectural design of these dwellings is particularly impressive. The mammoth bones—skulls, ribs, tusks, and other large skeletal components—were arranged in circular formations, creating dome-shaped structures. These skeletal frameworks were likely covered with animal hides, turning them into insulated living spaces capable of withstanding the brutal cold of the Ice Age. The thoughtful placement of each bone indicates that this was not a trial-and-error process but a carefully planned architectural solution to an unforgiving environment.

Yet, the Mezherich site offers more than architectural innovation. Inside the huts, archaeologists discovered a wide array of artifacts that provide an intimate look at the lives of these prehistoric inhabitants. These weren’t just places to sleep or take shelter—they were homes filled with culture, artistry, and evidence of a rich social life.

Among the most fascinating discoveries were ornaments made of amber and marine shells. These materials were not native to the region, suggesting that the people of Mezherich either traveled great distances or participated in early trade networks to acquire them. This implies a level of social organization and mobility that challenges many assumptions about prehistoric life. Additionally, a large bone, believed to have functioned as a drum, was found decorated with red ochre. This detail points to the presence of music and ritual, hinting at a ceremonial life that went beyond mere survival. These ancient people weren’t just enduring the Ice Age—they were living fully within it, expressing themselves and connecting with others.

Perhaps the most groundbreaking find at the site was a bone engraved with markings that many experts interpret as one of the earliest known maps. This remarkable artifact suggests that the people of Mezherich had a sophisticated understanding of their surroundings. They were not just reacting to their environment—they were mapping it, planning around it, and possibly communicating that knowledge to others. It offers an early glimpse into spatial intelligence and geographic awareness, hallmarks of human cognitive development.

The legacy of Mezherich is profound. These mammoth bone huts stand today not just as remnants of ancient architecture, but as symbols of human ingenuity and resilience. At a time when survival demanded every ounce of creativity and adaptation, our ancestors rose to the occasion with remarkable innovation. They didn’t just adapt—they thrived. Their structures, among the oldest known examples of human-built shelters, continue to inspire admiration and awe.

The Mezherich site remains a cornerstone of archaeological study, drawing scholars from around the world who seek to learn more about our prehistoric ancestors. Each artifact, each bone, and each engraving tells a story—one of survival, creativity, and a relentless pursuit of life in one of Earth’s harshest climates. These discoveries force us to rethink what we know about early humans. They weren’t simple cave dwellers grunting their way through life—they were builders, artists, traders, and thinkers.

Moreover, Mezherich challenges modern notions of innovation. In today’s world, we often associate ingenuity with technology and digital advancement. But the ancient people of Mezherich show us that true innovation is about using the resources at hand to overcome challenges. With no metal tools, no modern blueprints, and no written language, they managed to construct durable homes, express themselves through art and music, and possibly even chart their surroundings.

This extraordinary site reminds us of the deep roots of human intelligence and spirit. Long before skyscrapers and space travel, there were people on the frozen steppes of Ukraine, building homes out of bones and dreaming big under the endless Ice Age sky. Their story is our story—a testament to what humans can achieve even when faced with the most daunting odds.

As we continue to study Mezherich, it serves as a powerful reminder of how far we’ve come and how ingenious our species has always been. It invites us to look at the past not as a distant, primitive chapter, but as a rich source of inspiration. The ingenuity of Mezherich’s people echoes through time, proving that even 15,000 years ago, humans were already shaping the world with vision, courage, and imagination.