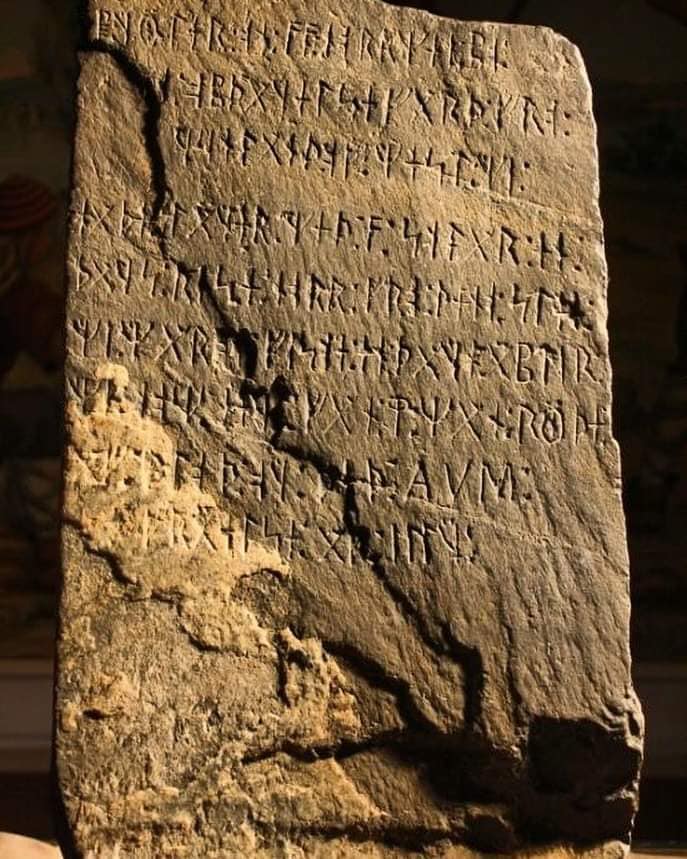

In 1898, a farmer in the small town of Kensington, Minnesota, made a discovery that would stir controversy for more than a century. While clearing his land of trees and stumps, Olof Öhman unearthed a large stone slab entangled in the roots of a poplar tree. What set this graywacke stone apart was its surface—it was covered in mysterious runic inscriptions. This artifact, which came to be known as the Kensington Runestone, quickly became the center of a historical debate that still divides scholars and history enthusiasts alike. The runes carved into the stone suggested something radical—that Norse explorers from Scandinavia had traveled deep into the interior of North America in the 14th century, long before Christopher Columbus made his famous voyage in 1492.

The runestone’s inscription is more than just a message; it’s a story—one filled with exploration, danger, and sorrow. According to the carved text, a group of “8 Goths and 22 Norwegians” set out on an expedition from a place called Vinland, a region many historians associate with Norse settlements in coastal North America, likely Newfoundland. Their journey took them far inland, where they camped out while a portion of the party went fishing. Upon returning, they were horrified to discover that ten of their companions had been killed. The inscription reads that they found the fallen men “red with blood and dead,” a chilling phrase that evokes the violence and uncertainty that must have haunted early explorers venturing into unfamiliar lands. The message ends with a prayer for their fallen friends and includes a brief note stating that the remaining members of the expedition were guarding their ship a day’s journey away.

If the Kensington Runestone is proven to be authentic, it would be one of the most important archaeological discoveries ever made in North America. It would drastically change our understanding of pre-Columbian transatlantic exploration. Currently, the widely accepted narrative is that Leif Erikson and other Norse explorers briefly settled in eastern Canada around 1000 AD, particularly at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland. But this runestone suggests a far more ambitious reach—into the heart of what is now the American Midwest. Such a discovery implies that Norse expeditions were not only capable of coastal navigation but also of traveling deep inland via river systems or over land, establishing temporary encampments, and perhaps even interacting with Indigenous peoples centuries before other Europeans arrived.

The controversy surrounding the Kensington Runestone has only grown since its discovery. From the beginning, scholars were split into two camps—those who believe in its authenticity and those who claim it’s an elaborate hoax. Supporters of the artifact argue that the style of the runes and the Old Norse language used in the inscription are consistent with what was known from 14th-century Scandinavian texts. They point to similar inscriptions found on authenticated Viking relics in Europe and argue that the farmer who discovered the stone would not have had the education or background to create such an intricate forgery, especially in rural Minnesota at the turn of the 20th century.

On the other hand, skeptics have voiced serious concerns. Linguists have identified what they consider anachronisms in the language—word forms and grammatical structures that didn’t exist in the 14th century but were present in 19th-century Scandinavian dialects, particularly those spoken by immigrants in Minnesota at the time. Additionally, some experts in stone carving argue that the chisel marks and wear on the runestone suggest a more modern origin. They question whether the stone could have survived over 500 years underground in such a well-preserved state, especially given the region’s harsh climate and shifting soils. Many skeptics believe the runestone may have been created by Scandinavian-American settlers, possibly even as a prank or a misguided attempt to establish a historical legacy for their community.

Despite extensive research, the mystery remains unsolved. Numerous scientific tests, including geological analysis of weathering patterns and microscopic studies of the carving’s depth and angles, have been conducted, but none have definitively proven the runestone’s age or authenticity. Over the years, it has inspired countless books, documentaries, and academic papers. Museums have featured it prominently, especially the Runestone Museum in Alexandria, Minnesota, where the artifact now resides. It has become both a historical curiosity and a cultural symbol—representing everything from Scandinavian-American heritage to the eternal human fascination with ancient mysteries.

Regardless of whether the Kensington Runestone is authentic or not, its impact is undeniable. It has captured the imagination of scholars, amateur historians, and the public alike, challenging established historical narratives and encouraging further exploration into early European contact with the Americas. In many ways, it serves as a reminder of how archaeology is not always about absolute answers but about expanding our perspective and being open to possibilities that may at first seem improbable.

The enduring intrigue of the Kensington Runestone lies not only in the message it bears but also in the questions it raises. Who carved it? What happened to the rest of the expedition? Did they ever return home? Or were they absorbed into Indigenous communities, their presence eventually lost to time? These are the types of questions that keep the debate alive and the story compelling.

In the end, the Kensington Runestone continues to be a powerful symbol of the unknown. Whether it’s a medieval relic or a clever 19th-century fabrication, its story has become part of the larger tapestry of American history. It stands as a testament to the power of discovery, the thrill of the unknown, and the ever-present possibility that history, as we know it, can still surprise us.