High in the icy heights of the Andes Mountains, where the air is thin and silence reigns supreme, a breathtaking archaeological discovery has offered the world an unparalleled glimpse into the past. In 1999, a team of archaeologists near the summit of Mount Llullaillaco—a towering volcano that straddles the border between Argentina and Chile—uncovered a find that would leave both the scientific community and the general public in awe. There, at an altitude of approximately 6,700 meters (22,100 feet), researchers unearthed the remarkably well-preserved remains of three Inca children, the most famous of whom has come to be known as the Llullaillaco Maiden.

This extraordinary discovery is widely considered one of the most significant in the field of high-altitude archaeology. The children, victims of an ancient Inca sacrificial rite known as capacocha, were found in a state of preservation so complete that it seemed as though they had only recently fallen asleep. Capacocha was a deeply spiritual ceremony conducted during moments of societal crisis or major transitions, such as droughts, famines, or the death of an emperor. It was believed that offering the most pure and noble children to the gods would help restore cosmic balance and secure divine favor. These ceremonies were not carried out in haste but were deeply ritualized, with great care taken in selecting the children, preparing them spiritually, and ensuring their sacrifice was conducted with honor.

Among the three children, the Maiden stood out not only because of her physical preservation but also due to the wealth of information her body and belongings provided. Estimated to be about 15 years old at the time of her death, she had been chosen for this sacred purpose likely years in advance. In the final months leading up to her sacrifice, scientists discovered that her diet shifted dramatically. Hair analysis showed a transition from a subsistence diet to one rich in elite foods such as maize and llama meat, which were reserved for nobility and religious ceremonies. This shift in nourishment marked her transition from an ordinary girl to a sacred offering, destined for the gods.

One of the most poignant discoveries was the detail of her final moments. Through forensic analysis, it was revealed that she was given coca leaves and a fermented maize-based alcoholic beverage, chicha, likely intended to sedate her and ease her passage from the world of the living. The presence of these substances suggests the Inca priests who oversaw the ceremony took measures to ensure she experienced as little fear or pain as possible. The evidence points to a peaceful death—one that underscores the spiritual seriousness with which the Inca approached these rituals.

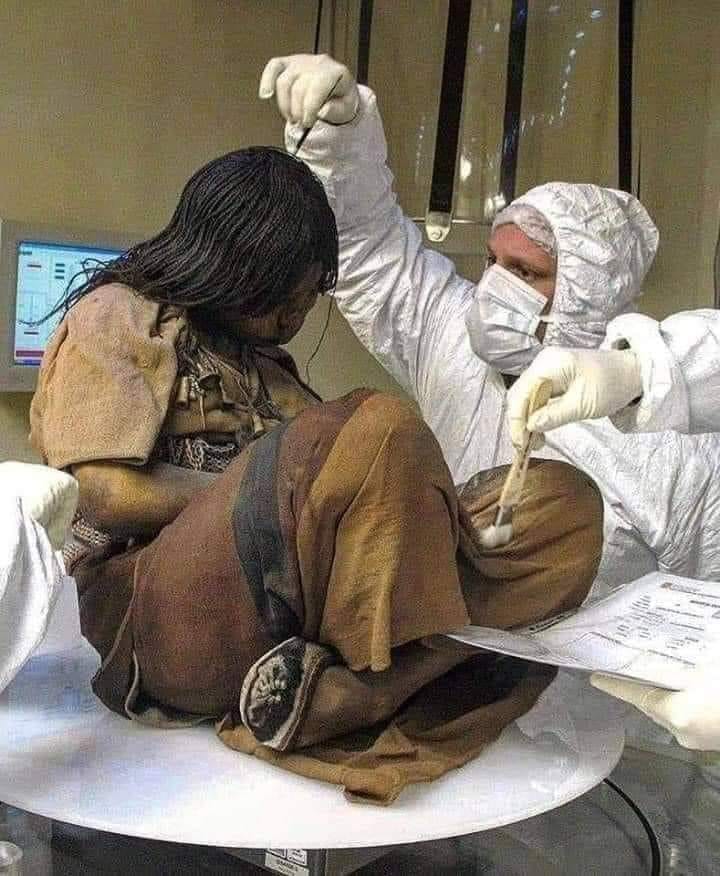

The conditions that led to the near-perfect preservation of the Maiden and the other two children are just as fascinating as the ceremony itself. The freezing temperatures, dry climate, and extremely low oxygen levels at that altitude created an ideal environment for natural mummification. Unlike artificial mummies, these children were not embalmed or chemically treated. Instead, their bodies were preserved by nature, with skin, hair, and even internal organs remaining intact for over 500 years. Her serene facial expression, intricately braided hair, and the vivid colors and patterns of her ceremonial garments have remained largely unchanged since the day she was placed in her icy tomb.

Accompanying her were various offerings that highlighted the immense craftsmanship and religious symbolism of the Inca civilization. Among these items were beautifully detailed miniature statues made from silver, gold, and shell, as well as finely woven textiles and decorated ceramic vessels. These objects were not mere accessories but carried significant cultural and religious weight. Each artifact tells a story about the beliefs and values of the Inca people, particularly their understanding of life, death, and the divine.

Today, the Llullaillaco Maiden and the other two mummified children are housed in the Museum of High Altitude Archaeology (MAAM) in Salta, Argentina. The museum is committed to preserving and presenting these remains with the utmost dignity and respect. The display is carefully curated to balance public education with cultural reverence, ensuring that visitors understand not just the scientific marvel of the discovery but also the spiritual and emotional weight carried by these children and their story.

The museum’s approach is centered on honoring both the scientific contributions and the cultural origins of the mummies. By doing so, it opens a window into the complexities of Inca religion, social structure, and their extraordinary capability to perform elaborate rituals at such extreme elevations. The high-altitude locations of these ceremonies were believed to bring the children closer to the gods, symbolizing a physical and spiritual ascension. This blending of geography, spirituality, and sacrifice reveals just how interconnected the Inca’s worldview was.

The Llullaillaco Maiden stands as a powerful symbol—not only of a civilization that reached incredible heights, both literally and figuratively—but also of the ways in which ancient peoples understood their place in the universe. Her story is not just one of death, but of purpose, belief, and the deep cultural reverence that framed life and the afterlife in Inca society. She reminds us that archaeology is not merely about objects or remains; it is about understanding people, their values, and the stories they left behind. In every strand of her braided hair and every thread of her ceremonial clothing, we find echoes of a civilization that lived in harmony with its gods and sought meaning in the cycle of life and death.

As researchers continue to study the Llullaillaco Maiden and her companions, new insights will no doubt emerge, deepening our appreciation for the richness and complexity of the Inca Empire. But even now, decades after her discovery, she continues to inspire awe and reflection—standing silently, yet powerfully, as a frozen bridge between our world and one that came long before.