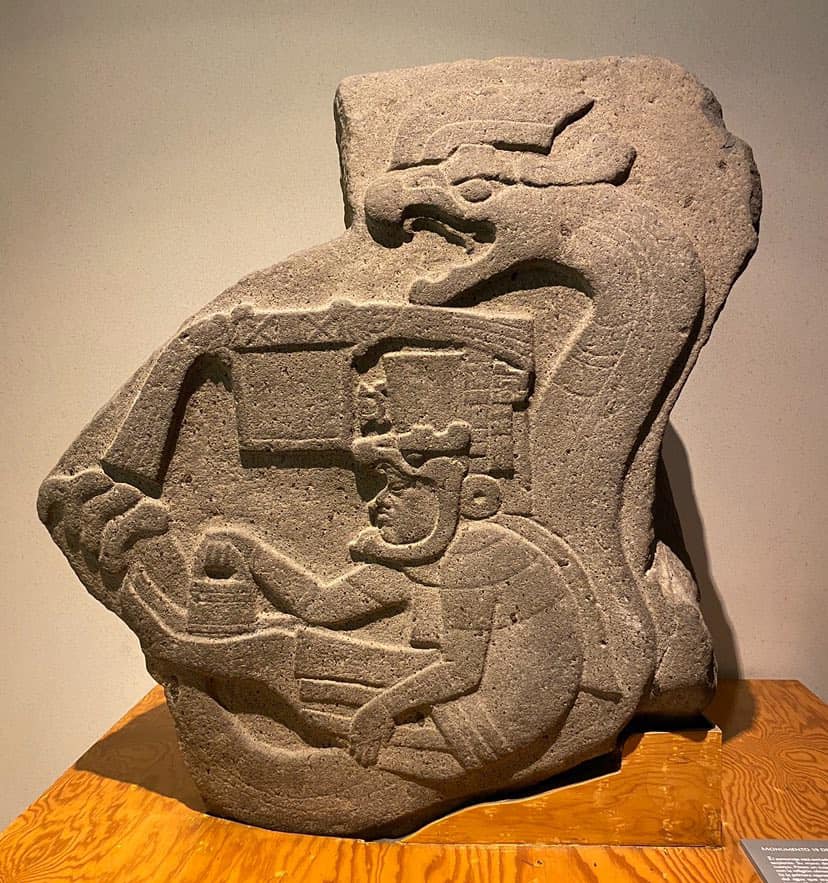

In the depths of ancient Mexico, where the roots of Mesoamerican culture first took hold, there lies a remarkable artifact that has fascinated archaeologists and historians for generations. Known as Monument 19, this extraordinary stone carving from La Venta, an Olmec ceremonial center, dates back to between 900 and 400 BC. It is more than just a relic of the past—it’s a window into the spiritual life, symbolism, and cultural foundations of one of the oldest civilizations in the Americas. Monument 19 stands as a powerful reminder of the Olmecs’ intellectual and artistic achievements, as well as their profound influence on later Mesoamerican societies.

Carved with striking detail and purpose, Monument 19 contains what is believed to be the earliest known depiction of the feathered serpent, a sacred symbol that would later permeate the mythologies and religions of countless Mesoamerican peoples. This serpent, draped in feathers, combines the primal power of the snake with the celestial symbolism of the bird, creating a fusion of earth and sky that was deeply meaningful to the Olmecs. The carving shows a human figure—possibly a ruler or shaman—interacting with this majestic creature in a scene rich with spiritual undertones. This moment, frozen in stone, speaks to the relationship between human authority and divine guidance, suggesting that the feathered serpent was not just myth, but a spiritual force woven into the very fabric of Olmec leadership and ritual life.

Unlike modern decorative symbols, the feathered serpent was not an aesthetic flourish. To the Olmecs, it represented key principles that governed life, death, and everything in between. It was a symbol of fertility, tied to the seasonal cycles and agricultural success. As a civilization dependent on the richness of the land, the Olmecs viewed this creature as a guardian of abundance. But its wings, representing the heavens, also gave the serpent a celestial quality—an ability to traverse between realms. This duality made it a bridge between the terrestrial and the divine, a unifying force that could embody both earthly vitality and cosmic order. Through this symbol, the Olmecs expressed their belief in harmony between humans, nature, and the spiritual world.

Over time, the feathered serpent’s legacy would only grow. In later Mesoamerican cultures, including the Maya and Aztecs, this figure evolved into gods such as Kukulkan and Quetzalcoatl, powerful deities of wisdom, creation, and transformation. But Monument 19 remains the starting point—the original testament to the spiritual imagination of the Olmecs. It shows that even in their early development, Mesoamerican civilizations were already contemplating complex ideas about divinity, leadership, and the afterlife. The fact that this carving predates all other known representations of the feathered serpent makes it a cornerstone for scholars trying to trace the development of religious thought in the region.

The reverence the Olmecs had for the feathered serpent is further evidenced by their burial practices and monumental architecture. Archaeological findings indicate that the symbol was closely tied to elite status and was possibly used to legitimize authority. Rulers may have claimed divine right through their association with this creature, positioning themselves as mediators between their people and the gods. Additionally, the serpent’s association with death and the afterlife suggests it was seen as a spiritual guide, capable of navigating the soul through the mysterious realm beyond life. In this way, the feathered serpent was not merely a symbolic figure—it was a sacred entity with the power to confer legitimacy, guide transitions, and protect spiritual integrity.

Monument 19, carved from basalt, is an artistic marvel in its own right. The technical skill required to create such detailed imagery using primitive tools is a testament to the Olmecs’ craftsmanship. But beyond its physical form, the carving’s deeper significance lies in its ability to communicate across time. Thousands of years later, we are still able to decipher its themes, analyze its implications, and appreciate the narrative it presents. The monument captures a snapshot of cultural development that helps piece together the broader mosaic of Mesoamerican civilization. It reminds us that the Olmecs were not a mysterious, lost people, but rather active architects of ideas and beliefs that would echo through generations.

Today, Monument 19 continues to inspire awe and curiosity. It is studied not only by archaeologists but also by historians, artists, and spiritual thinkers seeking to understand the origins of sacred symbols and cultural identity in the Americas. The feathered serpent, once an obscure image etched in stone, now stands as a unifying thread that connects diverse cultures across centuries. Its presence in later mythologies demonstrates the strength and adaptability of Olmec religious thought, proving that their influence was not only foundational but transformative.

As we reflect on Monument 19, we’re reminded of the profound ways in which ancient symbols continue to shape our understanding of the world. This single artifact bridges vast stretches of time, linking modern researchers with a civilization that vanished millennia ago. It offers insights not only into the lives and beliefs of the Olmec people but also into the universal human need to find meaning in nature, leadership, and the mysteries of existence.

Ultimately, Monument 19 is more than just a piece of carved stone—it’s a testament to the enduring power of spiritual expression, a record of a people who looked to the heavens and the earth in search of balance, prosperity, and divine connection. In honoring their legacy, we not only uncover the past but enrich our own appreciation of human creativity, resilience, and faith.