In 1506, amidst the thriving vineyards of ancient Rome, a discovery was made that would forever change the world of art and archaeology. Buried in the soil near the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, one of history’s most celebrated sculptures was unearthed—the Laocoön Group. This breathtaking masterpiece has continued to mesmerize art enthusiasts and historians with its vivid depiction of human suffering and unparalleled artistic craftsmanship. Now housed in the prestigious Vatican Museums, the Laocoön Group remains a testament to the power of art to transcend time, captivating generations as they seek to unravel its mysteries and appreciate its enduring beauty.

The rediscovery of the Laocoön statue marked a significant moment in the Renaissance, igniting excitement across Europe and drawing attention to the grandeur of ancient art. The statue was found in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis, and news of the discovery quickly reached Pope Julius II. Recognizing the potential importance of the find, the Pope sent prominent artists of the era, including Michelangelo, to inspect the statue. Their unanimous awe confirmed the statue’s significance, and the Pope swiftly acquired it, securing its place in the Vatican. Its public display soon began, allowing it to inspire countless artists and thinkers for centuries to come.

The Laocoön Group has been attributed to three Greek sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus. This attribution, first mentioned by the Roman writer Pliny the Elder, underscores the enduring legacy of ancient Greek artistry. While Pliny failed to provide an exact date for the statue’s creation, modern scholars have debated whether the work is an original Greek creation or a Roman copy of an earlier Greek bronze. The prevailing belief is that it represents the Hellenistic baroque tradition, known for its dynamic compositions, intricate details, and emotional intensity.

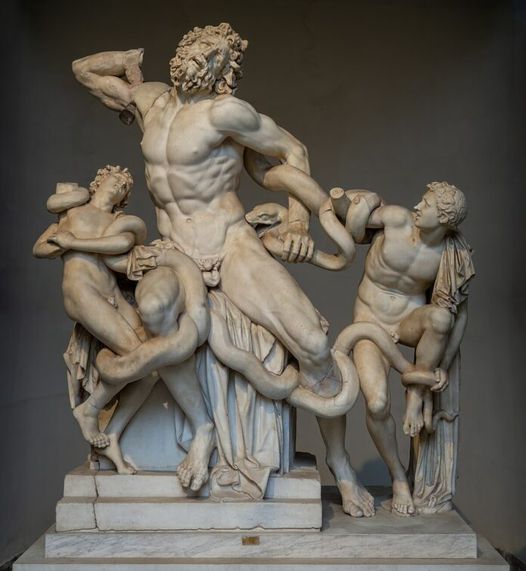

The subject of the Laocoön Group is steeped in mythology and drama, depicting Laocoön, a Trojan priest, and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, in the throes of a deadly attack by sea serpents. The nearly life-sized figures are masterfully crafted to convey raw and unrelenting agony. Laocoön’s anguished expression, complete with furrowed brows and contorted muscles, is often noted as physiologically exaggerated, yet it captures an emotional depth that transcends realism. This portrayal of suffering is stripped of any hopeful resolution, a stark contrast to the redemptive themes often found in Christian art.

The sculpture’s composition exemplifies the artistic principles of the Hellenistic baroque style. Every aspect of the Laocoön Group is imbued with movement and tension, from the twisting serpents to the desperate struggle of Laocoön and his sons. The piece invites viewers to experience the intensity of the moment, evoking both awe and empathy. Although Greek in origin, the Laocoön Group likely graced the home of an affluent Roman patron, possibly even someone within the Imperial family. Scholars estimate its creation to fall between 200 BC and the early Julio-Claudian period, around 70 AD.

The story behind the sculpture is as compelling as its artistry. The myth of Laocoön has been recounted in various ancient texts, each offering a unique perspective on his tragic fate. In Virgil’s Aeneid, Laocoön is portrayed as a priest of Poseidon who attempts to warn the Trojans of the Greek ruse involving the Trojan Horse. For his defiance, he and his sons are attacked by sea serpents, a punishment orchestrated by the gods. In another account, featured in the now-lost tragedy by Sophocles, Laocoön is depicted as a priest of Apollo who suffers divine wrath for breaking his vow of celibacy. These differing versions of the tale highlight the moral ambiguity of Laocoön’s suffering, leaving scholars to debate its deeper meanings.

The discovery and interpretation of the Laocoön Group have had a profound impact on both art and archaeology. Its unearthing in Renaissance Rome reignited interest in classical antiquity, inspiring artists like Michelangelo and Raphael to emulate its dramatic forms and emotional depth. The sculpture also played a pivotal role in shaping modern understanding of Hellenistic art, offering insight into the technical skill and cultural values of ancient sculptors.

For centuries, the Laocoön Group has remained a symbol of artistic brilliance and human resilience. Its ability to convey complex emotions through the medium of marble speaks to the timeless power of art to connect people across ages and cultures. As visitors to the Vatican Museums gaze upon this ancient masterpiece, they are reminded of the enduring legacy of the classical world and its influence on the art and ideas that define humanity.

Even today, the Laocoön Group continues to captivate audiences with its blend of myth, history, and artistry. It serves as a bridge between past and present, inviting us to reflect on the universal themes of struggle, sacrifice, and the inexorable passage of time. Whether viewed as a Greek original or a Roman interpretation, the Laocoön Group remains one of the most important works of ancient sculpture, a masterpiece that challenges and inspires in equal measure.

The Laocoön Group is more than just a work of art; it is a window into the world of antiquity. It offers a glimpse into the artistic practices, cultural narratives, and philosophical inquiries of the ancient world. Its discovery and preservation serve as a reminder of the rich history that lies beneath our feet, waiting to be uncovered and shared with future generations. In this way, the Laocoön Group stands not only as a testament to the skill of its creators but also as an enduring symbol of humanity’s quest to understand and appreciate the beauty of its shared heritage.