In the softly lit corridors of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the mummy of Queen Nodjmet rests silently yet powerfully, embodying the grandeur and mystique of ancient Egypt’s 21st Dynasty. Her remarkably preserved remains serve as an extraordinary window into the funerary customs of a time often overshadowed in the broader narrative of Egyptian history. As visitors walk past her resting place, they are transported to the Third Intermediate Period, a complex era of political flux and religious significance. Queen Nodjmet’s story, told through both her physical preservation and the artifacts found alongside her, reveals layers of culture, devotion, artistry, and resilience that defined ancient Egyptian royal life.

Nodjmet was far more than a royal consort; she was a woman of high status, deep religious connection, and possible royal blood. Believed by scholars to be the wife of Herihor, the powerful High Priest of Amun in Thebes, she may also have been the daughter of Pharaoh Ramesses XI, which would place her at the crossroads of Egypt’s declining New Kingdom and the dawn of a new socio-religious order. Throughout her life, she held several prestigious titles—Lady of the House and Chief of the Harem of Amun—positions that suggest a combination of domestic authority and religious influence. Her familial ties extended into the highest echelons of power, as she was the mother of Pinedjem I, who would later become both High Priest of Amun and de facto ruler of Upper Egypt. Nodjmet’s life was one immersed in the spiritual and political heart of Egyptian society.

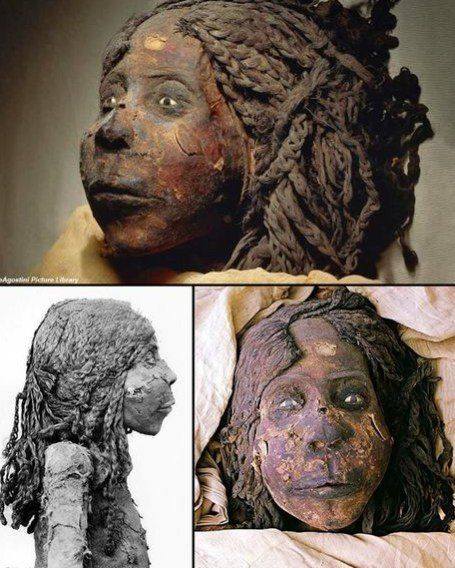

What sets Queen Nodjmet apart from other royal mummies is the exceptional quality of her embalming—a hallmark of the 21st Dynasty’s revolutionary approach to mummification. This period witnessed a dramatic shift in how the dead were prepared for the afterlife. Embalmers strove not just to preserve but to recreate a lifelike appearance that symbolized the deceased’s readiness for the next world. In Nodjmet’s case, these techniques reached an impressive level of sophistication. Artificial eyes made from polished white and black stones were set into her eye sockets, giving her a lifelike gaze. A carefully crafted wig and eyebrows, fashioned from real human hair, adorned her face to recreate her appearance in life. Her embalmers had padded her face and limbs to restore the fullness of youth and vitality, while coloring was applied to her skin to simulate a vibrant complexion. These details weren’t merely aesthetic—they represented a spiritual ideal. Ancient Egyptians believed that preserving the body in a complete and beautiful form was essential for a successful journey through the afterlife.

The discovery of Queen Nodjmet’s mummy in the Royal Cachette of Deir el-Bahari, known as DB320, added to her mystique and historical significance. This hidden tomb, uncovered in the late 19th century, was a secretive resting place for many royal mummies, concealed by priests to protect them from tomb robbers during times of unrest. Alongside her remains were a number of remarkable funerary objects, including two richly illustrated Books of the Dead. One of these sacred texts was written on a papyrus over four meters long—an exquisite piece of ancient Egyptian literature and theology now housed in the British Museum. These scrolls were not merely decorative but contained spells, prayers, and incantations meant to guide Nodjmet safely through the challenges of the afterlife, helping her soul to navigate the underworld and achieve eternal life among the gods.

In modern times, advanced scientific tools have provided even greater insights into Nodjmet’s life and death. CT scans have revealed detailed aspects of her embalming and health, while DNA analyses are helping researchers piece together her lineage and possible relationships to other members of the royal family. These methods allow us to look past the bandages and examine the woman herself—her age, her physical condition, and even the causes of her death. What emerges is not a mythical figure, but a real person who lived, ruled, and died in a turbulent era. Her body tells a story of both reverence and fragility, preserving evidence of ancient medical practices and beliefs, as well as the artistic skill of the embalmers who worked to grant her immortality.

However, the marks on her mummy also speak of a more somber reality. Despite the care taken in her burial, Queen Nodjmet’s tomb did not escape the fate that befell many ancient graves. Thieves, driven by greed and disregard for sacred tradition, had once broken into her final resting place. Cuts on her forehead, nose, and cheeks suggest that they were searching for valuable amulets or jewelry that might have been hidden beneath the wrappings. The absence of certain artifacts and the faint impressions of stolen items, such as a bracelet once worn on her right arm, illustrate the chaotic and dangerous times during which these royal burials were plundered. Yet, even in violation, her body continues to reveal history—marking the tension between reverence for the dead and the harsh realities of political and economic instability.

Queen Nodjmet’s legacy reaches far beyond the walls of a museum. Her mummy stands as a cultural touchstone, linking the modern world to a civilization that deeply believed in life after death and the sacred duty of preserving the dead. Her image, painstakingly restored by ancient hands, symbolizes a collective yearning for eternity and the conviction that death was not the end, but the beginning of a new journey. Her preservation is not only a technical feat—it is a spiritual achievement rooted in values that shaped the Egyptian worldview for thousands of years.

As we study Queen Nodjmet today, whether through ancient texts or modern scans, we do more than uncover facts—we reconnect with a society rich in artistry, symbolism, and human complexity. Her life, death, and preservation embody the ancient Egyptians’ deepest beliefs and offer a profound sense of continuity between the past and present. In every detail of her mummy, from the artificial eyes to the final resting pose, we see the timeless human desire to be remembered, honored, and prepared for whatever lies beyond this world. Queen Nodjmet’s story remains a vivid reminder of a civilization that refused to let death silence its most revered voices.