The Piombi Prison, located in the attic of the Doge’s Palace in Venice, Italy, stands as a remarkable example of a historical detention facility that differs significantly from typical medieval or Renaissance-era prisons. Unlike the dark, underground dungeons often associated with historical incarceration, the Piombi was situated directly beneath the palace’s lead-lined roof, giving it its name—“piombi” meaning lead in Italian. This unique positioning set it apart from the lower, damp, and insufferable cells found in other historic prisons. While the Piombi may have avoided the issues of excessive moisture and cold that plagued many subterranean prisons, it had its own set of hardships—intense heat in the summer months due to its proximity to the roof. The lead covering absorbed the sun’s rays, transforming the prison into an unbearable furnace during the height of summer, while in winter, the cold would seep through, making survival equally challenging.

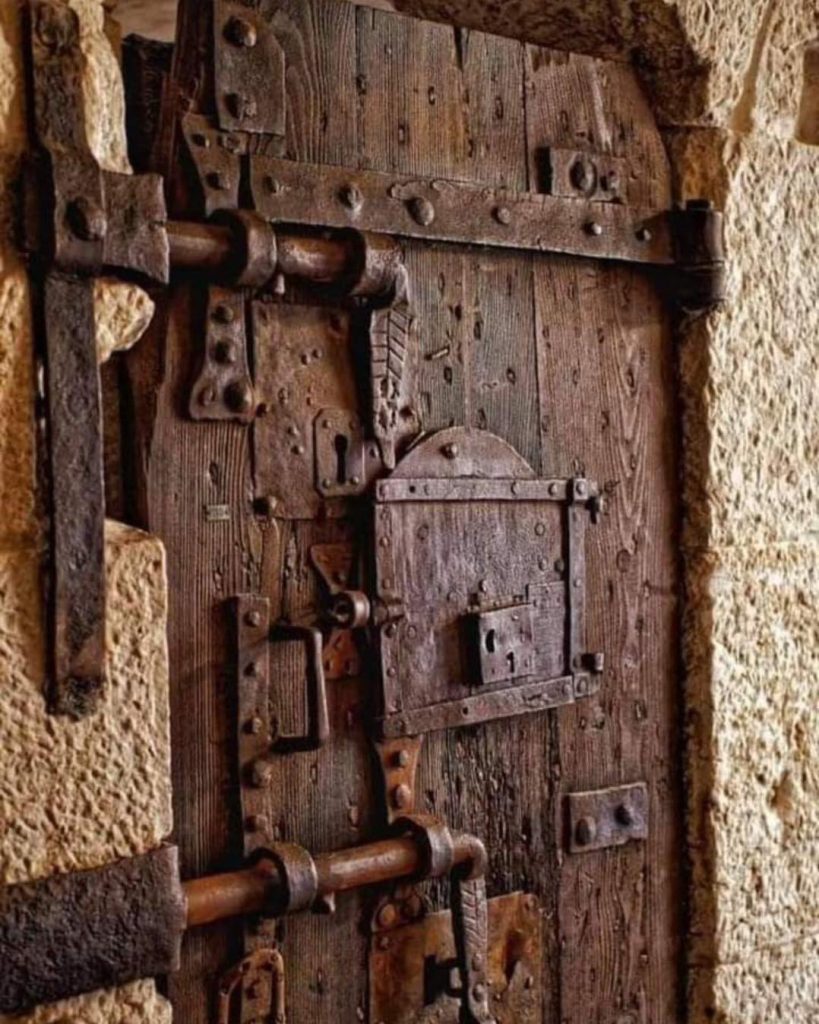

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Piombi is the artistry present in its construction. Unlike the crude and purely functional cells found in many prisons of its time, the ironwork on the doors of Piombi was intricately crafted. The deadbolts, for example, featured handles shaped like leaves—an artistic touch that seems unexpected in a place designed for confinement and punishment. This detail highlights the Renaissance Venetian approach, where even objects intended for the most grim purposes were not entirely devoid of aesthetic considerations. The Venetians, known for their skill in metalwork, ensured that even the locks and reinforcements of these prison doors reflected their craftsmanship.

The structure of the Piombi consisted of six distinct rooms, each separated by wooden partitions that were reinforced with iron plates. This design not only served as a security measure but also ensured that the walls remained durable despite the extreme temperature fluctuations. Access to these cells was restricted and could only be reached via two staircases. One of these staircases was situated in the Sala dei Tre Capi, which translates to the Room of the Three Chiefs, an important chamber where high-ranking officials convened. The second staircase was positioned in a corridor near the Sala degli Inquisitori di Stato, or the Hall of the State Inquisitors. This latter room was a significant space in Venetian governance, serving as a chamber where matters of state security and legal inquisitions were conducted.

Throughout its history, the Piombi housed numerous notable prisoners, some of whom were high-profile figures who found themselves at odds with the Venetian Republic. Among the most famous individuals held within these attic cells was Paolo Antonio Foscarini, a theologian whose works drew controversy. However, perhaps the most renowned prisoner to be confined in the Piombi was Giacomo Casanova, the infamous adventurer, writer, and master of seduction. Casanova’s imprisonment in the Piombi is particularly legendary due to the dramatic and daring escape he orchestrated—an event that has since been immortalized in historical accounts and literature.

Casanova, imprisoned in 1755, was accused of various offenses, including spreading heretical ideas and engaging in behavior that scandalized Venetian authorities. However, his daring escape from the Piombi in 1756 remains one of the most captivating prison breaks in history. Using a combination of ingenuity, patience, and assistance from a fellow inmate, Casanova managed to dig his way through the ceiling of his cell and make his way to the rooftops of the Doge’s Palace. From there, he navigated his way down and ultimately secured his freedom—a feat that added to his already notorious reputation.

The Piombi’s role in Venetian history is deeply tied to the Serenissima Republic’s approach to law and order. Unlike other European powers that relied on brutal public punishments, Venice employed a more calculated system of justice that often involved secret trials and high-security imprisonment. The State Inquisitors, who oversaw many cases, held significant authority and had the power to determine the fate of those accused of crimes against the Republic. The placement of the Piombi within the Doge’s Palace further emphasized the intertwining of political power and justice in Venice—where those who opposed the state could be held just beneath the very roof where laws were made and enforced.

Despite its grim history, the Piombi prison has fascinated historians, travelers, and scholars for centuries. The structure itself remains a testament to Venetian ingenuity, blending security measures with artistic elements, and its association with legendary figures like Casanova adds an undeniable aura of intrigue. Today, visitors to the Doge’s Palace can step into the very spaces where prisoners were once confined and imagine the stark realities faced by those who spent their days beneath the oppressive lead-lined roof.

The survival of these prison structures allows modern audiences to reflect on the evolution of justice and punishment throughout history. The Piombi, while not as torturous as some medieval dungeons, still represented a harsh reality for those imprisoned within its confines. The extreme conditions—sweltering summers and freezing winters—combined with isolation from the outside world made incarceration a brutal experience. Yet, within these walls, some of the most brilliant minds of the era continued to think, plot, and, in the case of Casanova, even plan an audacious escape.

Venice itself has always been a city of paradoxes—where beauty and brutality, art and discipline, power and secrecy coexisted. The Piombi prison exemplifies this duality, offering a glimpse into an era where governance was as much about spectacle and control as it was about justice. The existence of ornate ironwork on the doors of a prison is symbolic of this unique Venetian characteristic—where even the most utilitarian objects carried an artistic touch.

Today, the Piombi remains one of the many historical highlights of the Doge’s Palace, drawing visitors who seek to understand Venice’s complex past. Walking through these old prison cells, one cannot help but be transported back in time, imagining the whispered conversations of prisoners, the clang of iron locks, and the oppressive heat from the lead-covered roof above. Each rusted bolt, each worn wooden partition tells a story of those who once occupied these attic cells—some unjustly, others justly condemned, but all sharing the same fate of captivity within one of Venice’s most famous prisons.

The legacy of the Piombi endures not just because of its infamous prisoners but because it represents a distinct chapter in Venice’s approach to law and incarceration. Whether viewed as a place of punishment, an architectural relic, or a backdrop for one of the most legendary prison escapes in history, the Piombi stands as a reminder of the balance between power and justice in the Venetian Republic. Through its existence, we gain insight into the mechanisms of a once-mighty empire that ruled the Adriatic, blending artistry with authority, secrecy with spectacle, and punishment with prestige.