The Corinthian helmet, renowned for its iconic design, evokes a sense of romance and heroism as it is intrinsically linked to the legendary warriors of Ancient Greece. Despite advancements in helmet technology that provided improved visibility, the Ancient Greeks continued to depict their revered heroes wearing these distinctive helmets in art and literature. This enduring representation has cemented the Corinthian helmet as the quintessential symbol of Greek warriors in contemporary portrayals. However, modern adaptations often modify the design for aesthetic appeal, enhancing its dramatic and recognizable form for cinematic and artistic purposes.

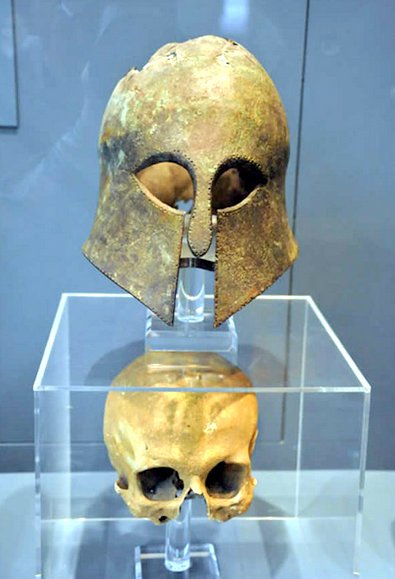

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) acquired a specific Corinthian helmet, cataloged as ROM no. 926.19.3, in 1926 from T. Sutton of 2 Albemarle Street, London, England. The acquisition occurred through an auction at Sotheby’s on July 22, 1926, listed under lot 160. Notably, the helmet was said to contain a skull (ROM No. 926.19.5), which heightened its historical intrigue. The helmet was originally excavated by George Nugent-Grenville, 2nd Baron Nugent of Carlanstown, on the Plain of Marathon in 1834. Correspondence from Sutton in August 1826 referenced the excavation, suggesting that this artifact had a documented history predating its sale. In addition to the Corinthian helmet, the auction lot also included a “Spartan-type” helmet (ROM no. 926.19.4) discovered by Nugent at Thermopylae in the same year. Nugent, who held the position of High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands from 1832 to 1835, played a significant role in acquiring these artifacts. They were later passed down through the Boileau family before being sold to Sutton, ultimately finding their way into the ROM collection.

The Battle of Marathon in 490 BC remains one of history’s most decisive conflicts. In this battle, the Greek forces achieved a landmark victory against the invading Persian army, an event that fundamentally shaped the course of Greek civilization and its classical era. Nugent’s particular interest in the artifacts from Thermopylae suggests an association with the famous battle of 480 BC, where a small but determined Greek force, including the legendary 300 Spartans, made a valiant stand against the Persian invasion at the narrow pass. While there is no definitive confirmation that these helmets were directly involved in these battles, their discovery in these historically significant locations lends credibility to their connection. Nugent’s presence in Greece soon after its liberation from Ottoman rule during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1832) makes his acquisitions all the more plausible, particularly as the British Navy played a crucial role in Greece’s struggle for sovereignty.

Determining the authenticity of the association between the skull and the helmet presents considerable challenges. Since the Greeks emerged victorious at Marathon, it is unlikely that they would have left behind the remains of their fallen warriors or usable equipment. Additionally, analysis of the helmet indicates that the damage it sustained was more likely due to the natural aging of the metal rather than battle-related impact. The prospect of a helmet remaining with the head it once protected is highly improbable. Nonetheless, while the helmet and skull were found together, it cannot be entirely ruled out that the skull belonged to the original wearer. A significant gap of nearly a century between the excavation and the documented acquisition of these artifacts introduces considerable uncertainty regarding the accuracy of historical records. This uncertainty is compounded by the fact that Nugent’s descendants did not inherit his personal collections, making the provenance more difficult to verify. Although a DNA analysis and radiocarbon dating of the skull could potentially provide clarity on its origins, such studies are not currently planned due to preservation concerns and funding constraints.

The construction and physical characteristics of the Corinthian helmet provide valuable insights into its function and craftsmanship. When researchers examined the Nugent Marathon helmet, they sought to provide detailed information to Matt Lukes, a craftsman specializing in historical replica equipment for reenactors. Lukes aimed to recreate an accurate representation of the Corinthian helmet using traditional methods. The study focused on determining whether the helmet had been formed by raising a bronze sheet, a process that would facilitate replication through modern spinning techniques on a lathe. This method would allow for the creation of a bowl-like shape that could then be further refined to match the contours of the original helmet. The examination also revealed variations in the helmet’s thickness, which played a crucial role in its protective qualities. The face section was found to be relatively thick, measuring between 2 mm and 3 mm, with the nasal guard reaching up to 10 mm in thickness. Conversely, the back and crown of the helmet were significantly thinner, measuring less than 1 mm. This strategic variation in thickness provided enhanced protection for the face while maintaining a manageable weight. The design was particularly suited for the hoplite style of warfare practiced by the Ancient Greeks, where spear thrusts were commonly used in conjunction with large, round shields to form formidable phalanx formations.

The Corinthian helmet exemplifies the remarkable craftsmanship of Ancient Greek armorers. Designed to provide maximum protection for the wearer’s face while allowing mobility and functionality in battle, it became an essential component of Greek military attire. Its distinctive shape, featuring a pronounced nose guard and extended cheek plates, provided a formidable appearance that was as intimidating as it was effective. Despite its protective advantages, the helmet’s limited visibility eventually led to the development of alternative designs, such as the Chalcidian and Attic helmets, which offered improved peripheral vision while still maintaining a degree of facial protection. Nevertheless, the enduring image of the Corinthian helmet remains synonymous with Greek warriors, immortalized in classical sculpture, pottery, and historical texts.

The broader cultural and symbolic significance of the Corinthian helmet cannot be overlooked. Beyond its practical function as battlefield armor, it became emblematic of heroism and valor. In Ancient Greek art, warriors and deities alike were frequently depicted wearing Corinthian helmets, reinforcing their association with martial prowess and divine favor. This visual representation persisted even as helmet designs evolved, underscoring the helmet’s role as a powerful cultural icon. Modern adaptations in film, television, and literature continue to draw upon this imagery, perpetuating the legacy of the Corinthian helmet as an enduring symbol of Ancient Greek military might.

In conclusion, the discovery of this Corinthian helmet, potentially linked to the Battle of Marathon, offers an intriguing glimpse into the military history of Ancient Greece. While uncertainties remain regarding its precise origins and the enigmatic skull associated with it, the artifact continues to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike. Its design, construction, and historical significance provide valuable insights into the warfare and culture of the Greek classical period. The Corinthian helmet stands as a testament to the skill of ancient armorers, the valor of Greek warriors, and the enduring fascination with this remarkable period in history. Whether viewed as a relic of battle or a symbol of heroic legend, the helmet remains an object of profound historical and artistic importance, bridging the past with the present and preserving the legacy of Ancient Greek civilization for future generations.