The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 was a momentous event in the field of archaeology. Hidden in the Valley of the Kings for over 3,000 years, the tomb was nearly untouched, providing scholars with an unprecedented glimpse into ancient Egyptian life, rituals, and burial customs. British Egyptologist Howard Carter, who led the excavation, had no idea what awaited him when he stumbled upon the sealed tomb. The wealth of artifacts, the mystery surrounding the young pharaoh, and the remarkable preservation of the burial chamber captivated the world. Fortunately, photographer Harry Burton was present to meticulously document the excavation. His images, now colorized by Dynamichrome, provide an unparalleled visual record of one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of all time.

Burton’s photographs, combined with Carter’s detailed journals, allow modern audiences to relive the moment of discovery. Carter’s words vividly describe the emotions of opening the tomb’s second door and peering inside for the first time. “It was some time before one could see,” Carter recorded, “the hot air escaping caused the candle to flicker, but as soon as one’s eyes became accustomed to the glimmer of light, the interior of the chamber gradually loomed before one, with its strange and wonderful medley of extraordinary and beautiful objects heaped upon one another.” His writings, paired with Burton’s images, create a rich historical tapestry that brings the moment to life.

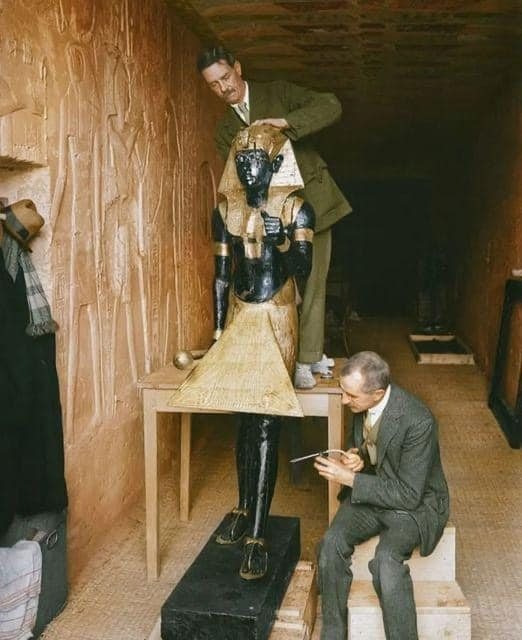

The photographs capture more than just the treasures— they also reveal the meticulous efforts of archaeologists as they cataloged, preserved, and studied the artifacts. Objects ranging from intricately carved statues and elaborate furniture to delicate garments and musical instruments were carefully tagged and arranged. Some images show the team of archaeologists at work, while others highlight the extraordinary relics uncovered in the burial chamber. Thanks to the Griffith Institute at the University of Oxford, Carter’s journals, Burton’s photographs, maps, and detailed inventory lists of the tomb’s contents remain accessible to researchers and history enthusiasts today.

Among the most iconic images is that of King Tutankhamun’s famous gold death mask. On October 29-30, 1925, Carter and his team uncovered the innermost solid gold coffin, where the mask was still in place on the king’s mummified body. The breathtaking craftsmanship and symbolic significance of the mask made it one of the most famous artifacts ever discovered. Another striking photograph, taken on December 2, 1923, shows Carter, Arthur Callender, and Egyptian workers dismantling the wall between the Antechamber and the Burial Chamber to access the four golden shrines enclosing the sarcophagus.

Other images provide glimpses of the careful unwrapping of the burial goods. On December 30, 1923, Carter, Arthur Mace, and an Egyptian workman can be seen rolling back the linen pall covering a gilded wooden frame between the first and second shrines. These moments illustrate the painstaking process of uncovering the tomb’s treasures while ensuring their preservation.

Burton spent eight years documenting the excavation, capturing everything from grand discoveries to intricate conservation efforts. His images reveal the vast array of objects found within the tomb. In December 1922, he photographed the west wall of the Antechamber, where items such as the cow-headed couch (Carter no. 73) and boxes containing preserved meats (Carter nos. 62a to 62vv) were stacked. A 1926 photograph showcases three wooden chests in the Treasury, one shaped like a cartouche, containing jewelry, sandals, and even a wax model of a heron.

The level of detail in Burton’s work is extraordinary. A November 1926 image highlights an array of model boats, symbolizing the king’s journey to the afterlife, neatly stacked against the southern wall of the Treasury. Another December 1922 photograph captures the northern wall of the Antechamber, where two life-sized sentinel statues stood guard over the burial chamber. Additional images show objects stored beneath a lion-shaped couch, including an ivory and ebony chest, shrine-shaped boxes, and an ebony child’s chair.

Beyond documenting the tomb’s riches, Burton also recorded the conservation efforts undertaken by Carter and his team. On November 29, 1923, Carter and his colleague Arthur Callender can be seen wrapping one of the sentinel statues of Tutankhamun before transferring it to a makeshift laboratory set up in the tomb of Sethos II (KV 15). These statues, positioned on either side of the Burial Chamber’s entrance, were crucial symbols of protection for the young pharaoh’s afterlife.

The conservation work continued in the laboratory. In late 1923, Burton captured Arthur Mace and Alfred Lucas stabilizing the surface of one of Tutankhamun’s state chariots, found in the Antechamber. Another January 1924 photograph shows the same team working on one of the two sentinel statues, ensuring it was properly preserved before being moved.

Burton’s photographs also reveal the complexity of the tomb’s architecture. A December 1923 image shows Carter, Callender, and two Egyptian workers lifting a roof section from the first, outermost shrine. This shrine, resembling a ‘sed festival pavilion,’ was constructed from twenty interlocking oak sections. Another iconic image from January 4, 1923, captures Carter kneeling in the Burial Chamber, looking through the open doors of the four gilded shrines toward the quartzite sarcophagus, the final resting place of King Tut.

Among the last images in the collection is a striking October 1926 photograph of the Anubis shrine, placed at the entrance of the Treasury. This shrine, topped with a statue of Anubis, the god of mummification, was covered with a linen cloth bearing the cartouche of Akhenaten. Another December 1923 photograph provides a close-up view of the linen pall inside the outermost golden shrine, decorated with bronze rosettes.

Burton’s extensive documentation ensures that this incredible chapter of history is preserved for future generations. His images, combined with Carter’s detailed notes, provide invaluable insight into one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of all time. The excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb not only revealed the splendor of ancient Egypt but also set new standards for archaeological fieldwork and artifact conservation.

Even today, the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb remains one of the most fascinating and celebrated moments in history. The photographs, colorized for modern audiences, bring the excavation to life, allowing us to step back in time and witness the wonders of an ancient world. Thanks to the meticulous efforts of Carter, Burton, and their team, the legacy of King Tut endures, providing an everlasting connection to the grandeur and mystery of ancient Egypt.