For decades, the Tollund Man has captivated archaeologists and historians alike. As one of Europe’s most famous “bog bodies,” his remarkably preserved remains offer a rare glimpse into the past. Yet, despite extensive studies, many questions about his life—and death—remain unanswered. More than 2,000 years ago, this Iron Age man met a violent end, his body buried in a peat bog where the unique environmental conditions naturally mummified his remains. While the precise circumstances of his death are still debated, experts widely believe that his killing was a ritual sacrifice to the gods. As Joshua Levine noted in Smithsonian magazine in 2017, such sacrifices were not uncommon in ancient Europe, likely performed to secure divine favor or ensure fertility for the land.

Although much about his death remains uncertain, one aspect of his final moments is now definitively known: his last meal. A team of researchers led by Nina Helt Nielsen, director of research at Denmark’s Silkeborg Museum, recently conducted an in-depth analysis of the Tollund Man’s gut contents, uncovering new details about what he ate before he died. The findings, published in the journal Antiquity, reveal that his final meal consisted of a simple porridge and fish.

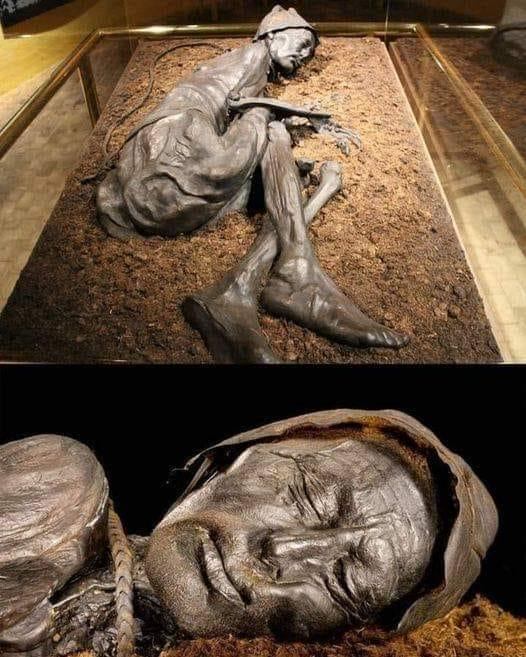

The discovery of the Tollund Man’s body in 1950 was nothing short of astonishing. Found in the Bjældskovdal peat bog in north-central Denmark, his remains were so well-preserved that authorities initially suspected a modern murder. His body, along with dozens of other bog bodies unearthed across Britain and northern Europe, provides a rare window into the past. The man, estimated to have been between 30 and 40 years old at the time of his death, was hanged sometime between 405 and 380 BCE. Even today, the leather noose remains wrapped around his neck. After his execution, his body was carefully placed in a sleeping position within a peat-cutting pit, suggesting a deliberate burial rather than a simple disposal.

Shortly after his discovery, researchers examined his digestive tract and determined that he had consumed his last meal roughly 12 to 24 hours before his death. However, scientific advancements over the last seven decades have allowed Nielsen’s team to reexamine the contents of his stomach with far greater precision.

“In 1950, researchers only analyzed the preserved grains and seeds, overlooking the finer material,” Nielsen explained to NBC News’ Tom Metcalfe. “Today, with better microscopes, improved analytical techniques, and new technologies, we can extract far more information.”

To reconstruct the Tollund Man’s diet, researchers meticulously examined both his large and small intestines, searching for decomposed plant remains—also known as macrofossils—as well as pollen samples, proteins, and other chemical traces. Their findings revealed that his last meal, though historically significant, was rather ordinary: a basic porridge made from barley, pale persicaria (a weed), and flax, accompanied by a small portion of fish. Traces of charred food crusts found in his gut suggest that the porridge was cooked in a clay vessel, indicating a level of culinary practice common in the Iron Age.

However, the analysis also revealed an unpleasant aspect of his digestive health. The Tollund Man was infected with three types of parasites, including tapeworms, likely contracted from drinking contaminated water or consuming undercooked meat. This discovery sheds light on the dietary and sanitary conditions of the time, suggesting that intestinal parasites were a common affliction.

The general consensus among archaeologists is that the Tollund Man was a victim of human sacrifice. Such ritual killings were likely performed to appease deities or ensure agricultural prosperity. Yet, one interesting aspect of his final moments is that he does not appear to have been given any special substances, such as hallucinogens or pain relievers, in preparation for his sacrifice. This contrasts with some other ritualistic burials, where evidence suggests the deceased were drugged or sedated before their deaths.

One lingering mystery is whether the people who buried the Tollund Man knew that his body would be so well preserved. Peat bogs create a unique preservation environment due to their high acidity, low oxygen levels, and cold temperatures. The presence of a specific type of sphagnum moss further aids the preservation process by producing chemicals that inhibit bacterial decay. This natural mummification effect essentially transforms soft tissues into a leather-like texture while keeping hair and nails intact. As Levine described in Smithsonian, these bogs act as “natural refrigerators” for human remains. Even today, the Tollund Man’s chin stubble and wool cap remain remarkably well-preserved, despite nearly 2,400 years passing since his death.

While his meal was largely unremarkable, researchers did identify one peculiar ingredient: threshing waste. This refers to a collection of wild seeds that were typically removed from grains during the threshing process. The presence of these seeds raises intriguing questions. Did early Iron Age people in Denmark add these castoffs to porridge as a means of increasing its nutritional value? Or were they included only for special occasions—perhaps as part of a ritualistic meal prior to sacrifice? The researchers can only speculate, as the available data remains limited.

As Nielsen noted in her interview with NBC News, deciphering these details with certainty is difficult. The Tollund Man, like other bog bodies, represents an unusual case. His death and burial circumstances were far from typical, making it challenging to draw broad conclusions about Iron Age society based on his remains alone.

Henry Chapman, an archaeologist at the University of Birmingham, echoed this sentiment in his comments to National Geographic. “Bog bodies are unusual. That’s both their blessing and their curse,” he explained. Because their preservation is so rare and their deaths often tied to unique circumstances—such as ritual killings—scientists must be cautious when using them as evidence to generalize about entire populations.

Despite the many remaining mysteries, each new discovery about the Tollund Man brings us closer to understanding life—and death—in the Iron Age. His simple last meal, the parasites in his gut, and the extraordinary preservation of his body all paint a vivid picture of a world long gone. As scientific methods continue to advance, perhaps future studies will unlock even more secrets hidden within the ancient peat bogs of Europe. Until then, the Tollund Man remains a haunting yet invaluable connection to humanity’s distant past.