In 1905, within the scorching sands of Egypt’s famed Valley of the Kings, an extraordinary discovery came to light—one that would astonish both the scholarly community and the wider public. British Egyptologist James Edward Quibell, during his excavations, unearthed Tomb KV46, the final resting place of Yuya and his wife Thuya. Though perhaps lesser-known to the general public today, this discovery stood as one of the most significant archaeological finds of the early 20th century and provided a rare, unfiltered look into the lives of Egypt’s powerful non-royal elite. The tomb’s wealth of artifacts and exceptional preservation of the mummies opened a unique window into the 18th Dynasty and offered invaluable insights into the court life and funerary practices of ancient Egypt.

Yuya was no ordinary man. Hailing from the city of Akhmim in Upper Egypt, he held high-ranking titles such as “King’s Lieutenant” and “Master of the Horse,” which denoted both his authority and his close proximity to royal power. His roles extended into religious and economic spheres as well. As a prophet of the fertility god Min and the “Superintendent of Cattle,” Yuya wielded considerable influence over temple rituals and state-owned livestock, critical sectors of Egypt’s wealth. Such titles reflect a man who was integral to the functioning of the royal court and temple economy—someone whose contributions were valued enough to merit an elaborate burial in the most sacred necropolis in Egypt.

Tomb KV46, for sixteen years before the discovery of Tutankhamun’s burial site, was considered the finest intact tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Although Yuya was not a pharaoh, the splendor of his tomb challenged traditional notions of royal exclusivity in such a prestigious burial ground. The wealth of items found within, ranging from chariots to intricate jewelry, suggested that Yuya and Thuya were not only esteemed figures in life but honored in death in a manner comparable to royalty. The craftsmanship of the artifacts, the variety of materials used, and the detail of the funerary goods all indicated the care and reverence with which this couple was interred.

Yuya’s mummy, in particular, became a subject of intense interest among early 20th-century archaeologists and anatomists. Sir Grafton Elliot Smith, a renowned anatomist and pioneer in the study of mummification, described Yuya’s remains as one of the most exceptional examples of 18th Dynasty embalming practices. His observations provide fascinating details that allow modern scholars to understand the techniques and cultural values surrounding death and preservation in ancient Egypt.

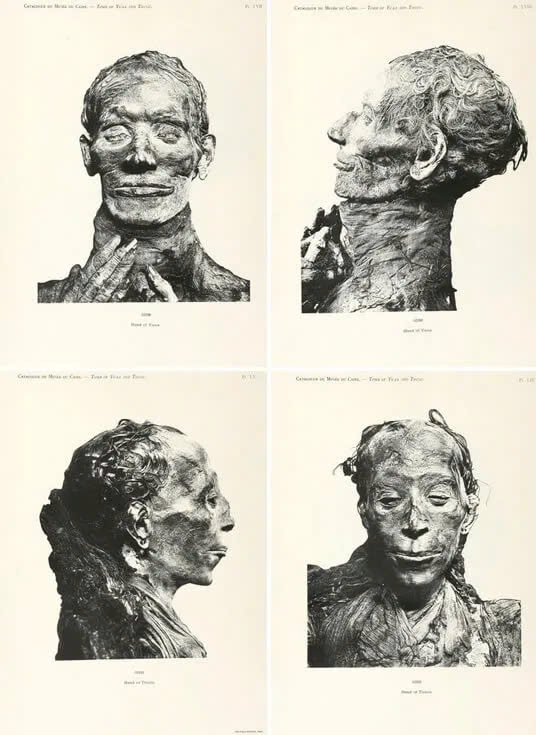

Yuya’s body was that of a man likely between 50 and 60 years old at the time of his passing. His hair, preserved in a yellowish hue with a distinct wavy texture, is believed to have been lightened due to exposure to embalming substances, possibly natron and resins. The embalmers filled the body cavity with linen soaked in resin, an approach that not only preserved the internal space but also provided structural integrity to the corpse. His arms were crossed over his chest—a posture commonly associated with nobility—and his fingers were fully extended, a rare feature in mummies, suggesting meticulous care in positioning. The eye sockets and eyelids had been attentively prepared to retain their natural shape, contributing to the mummy’s striking lifelike appearance.

Despite the tomb being subjected to ancient looting, the grave goods that remained were substantial. Among the most poignant finds was a partially strung necklace of gold and lapis lazuli beads, discovered tucked behind Yuya’s neck. This delicate artifact, a symbol of both wealth and artistry, hinted at the original splendor of the tomb’s contents and suggested that the robbers may have been interrupted or acted in haste. Such details allow us to imagine the chaos of the intrusion and the lingering traces of what was lost.

The preservation of both Yuya and Thuya’s facial features is nothing short of astonishing. More than three thousand years have passed since their deaths, yet their mummified remains retain a level of detail that allows modern viewers to connect, almost intimately, with these individuals from antiquity. Their faces, with contours, expressions, and subtle anatomical details still intact, serve as living portraits of ancient Egyptian aristocracy. It is this sense of immediacy—of standing face-to-face with people from a civilization long gone—that continues to captivate the imagination of scholars and enthusiasts alike.

The discovery of Tomb KV46 has proven invaluable in the study of ancient Egypt. Not only does it offer evidence of the wealth and status afforded to elite courtiers, but it also provides concrete data on burial practices, religious beliefs, and the intersection of politics and ritual in the 18th Dynasty. Moreover, it sheds light on the societal values of the time, demonstrating that individuals of exceptional service and connection to the royal family could achieve a burial comparable to that of kings.

Yuya and Thuya’s legacy, preserved through time and careful archaeological study, remains a testament to the opulence and reverence surrounding death in ancient Egypt. Their tomb, once filled with brilliant treasures and still echoing with stories of devotion and honor, connects us directly to a distant but enduring past. The faces that peer out from their sarcophagi are not merely relics of history—they are enduring symbols of a civilization that continues to fascinate and inspire the world.