The ancient stone walls of Sacsayhuamán in Peru have fascinated researchers, explorers, and engineers for generations. Situated high in the Andes at an elevation of around 3,500 meters (approximately 11,500 feet), these walls represent one of the most compelling mysteries of pre-Columbian construction. The sheer size, precision, and scale of the site push the boundaries of what we thought was possible for ancient civilizations. For decades, archaeologists and engineers have puzzled over how such a remarkable feat of construction could have been achieved without the aid of modern tools, advanced machinery, or even basic technologies like the wheel.

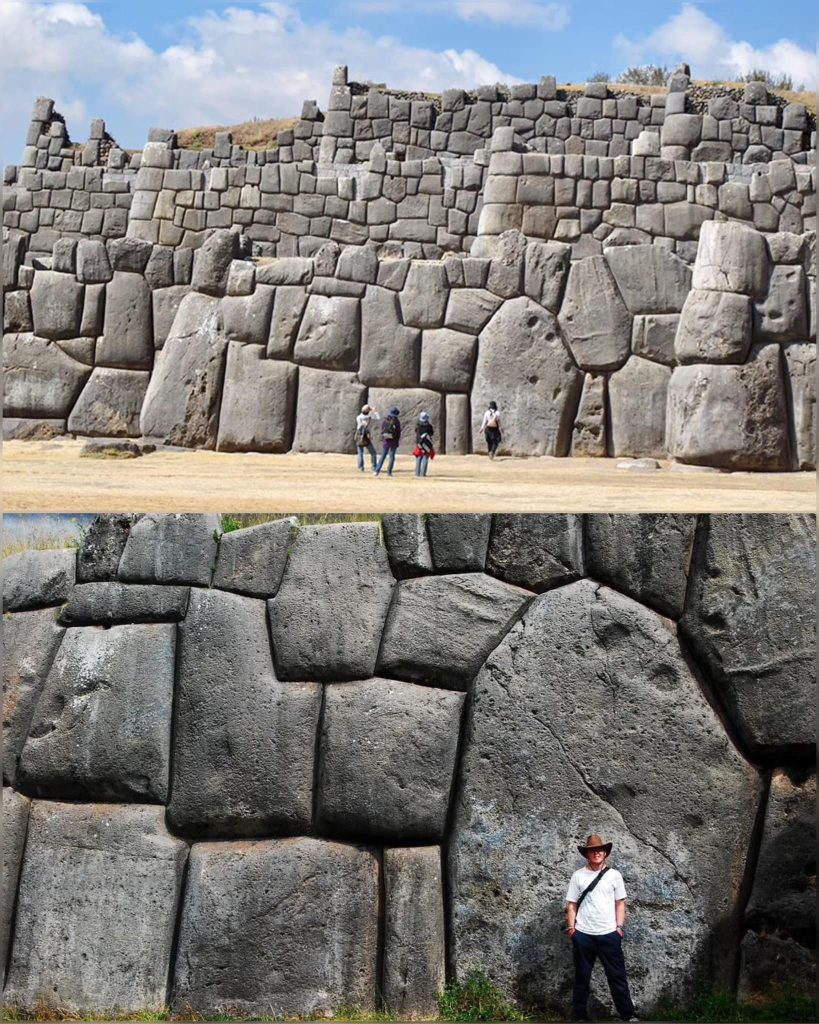

What makes Sacsayhuamán truly extraordinary is not just the magnitude of its construction but the way it was built. The walls are composed of enormous interlocking stones, some weighing upwards of 100 tons. These megaliths are cut and fit together with such precision that even a thin blade cannot slip between them. Remarkably, this architectural marvel was created by a society that lacked several critical elements of conventional engineering. They had no draft animals such as oxen or horses to transport heavy loads across the rugged terrain. The natural resources in the region did not include the kinds of sturdy timber or plant fibers typically used for ropes strong enough to handle such tasks. Furthermore, there is no archaeological evidence suggesting that these ancient builders had discovered or used wheel-based transport systems. Yet somehow, they managed to quarry, transport, shape, and set these massive stones in place with an accuracy that modern engineers still struggle to replicate.

In recent years, an alternative theory has emerged that may finally offer a plausible explanation for this ancient engineering enigma. A team of researchers from various universities across Central and South America has proposed a groundbreaking hypothesis that challenges the long-held assumption that these blocks were carved from natural rock. Instead, they suggest that the stones might actually be artificial — human-made geopolymers created by mixing raw materials and casting them on-site.

According to this theory, the ancient builders may not have had to move massive rocks at all. Rather, they could have transported smaller, more manageable amounts of raw material to the construction site and then chemically combined them to form large, synthetic stones. These geopolymers, if proven to be genuine, would possess physical properties similar to — or even better than — those of natural stone. The implication is revolutionary: instead of brute force and primitive methods, the people who built Sacsayhuamán may have possessed a high level of knowledge in chemistry and materials science, allowing them to create and mold stone as needed.

The concept of geopolymer construction is not entirely without precedent. In fact, there’s growing evidence to suggest that this method was used in other ancient civilizations as well. For example, the cladding of Snefru’s Bent Pyramid in Egypt has shown signs of being composed of synthetic materials rather than carved limestone. Similarly, microscopic analysis of certain blocks from the Great Pyramid of Giza indicates the presence of chemical signatures consistent with man-made stone. These findings suggest that the knowledge of creating geopolymers may not have been isolated to a single region. Instead, it could have been a shared or rediscovered technique developed independently by separate civilizations, each responding to their environmental and logistical challenges in innovative ways.

What makes this theory so compelling is not just its potential to explain the construction of Sacsayhuamán but also its broader implications for our understanding of ancient cultures. It invites us to reconsider the intellectual and technological sophistication of these societies. If ancient Peruvians had mastered such a complex form of chemistry, what else might they have known? What other knowledge or inventions might have been lost to time or misinterpreted through the lens of modern bias?

The idea that two vastly different civilizations — the builders of Sacsayhuamán in South America and the pyramid builders in North Africa — may have independently developed a similar approach to creating synthetic stone forces us to rethink how we view ancient innovation. Rather than seeing these cultures as isolated and underdeveloped, perhaps we should recognize them as dynamic, resourceful, and highly intelligent, capable of solving problems with remarkable creativity.

This hypothesis also encourages modern scientists and archaeologists to take a fresh look at ancient ruins around the world. It may prompt new testing methods, closer examinations, and interdisciplinary collaborations that could unearth further evidence of forgotten technologies. Moreover, it challenges us to reflect on the fragility of historical knowledge. Much of what we consider “known” about ancient civilizations is based on interpretations of physical remains, and those interpretations can change dramatically with the introduction of new evidence or perspectives.

If confirmed, the use of geopolymers at Sacsayhuamán would not only rewrite a chapter in the history of engineering but also restore a sense of awe for the achievements of ancient peoples. It would suggest that these early civilizations were not merely laborers bound by their limitations, but scientists and engineers in their own right. Their monuments were not just built with strength and endurance but with intellect, experimentation, and innovation.

In light of this, the walls of Sacsayhuamán stand as more than just a breathtaking example of ancient architecture. They become a symbol of human ingenuity — a silent, stone-bound testament to the capability of people to solve extraordinary problems with limited tools. These walls challenge us to reassess what we believe about the past and inspire us to explore the hidden depths of human knowledge that may still lie buried, waiting to be uncovered. The legacy of Sacsayhuamán is not just one of stone, but of the enduring brilliance of the human spirit.