In an astonishing breakthrough at Koobi Fora, a region near Kenya’s Lake Turkana, scientists have unearthed a set of fossilized footprints that offer an extraordinary glimpse into a time when two distinct early human species—Paranthropus boisei and Homo erectus—roamed the same landscape. These footprints, sealed in ancient mud and preserved for more than 1.5 million years, provide a rare and powerful connection to our prehistoric past. This discovery does more than merely inform us of the existence of these species; it invites us to visualize how they might have interacted with each other and coexisted in a shared environment, revealing key insights into early human behavior and adaptation.

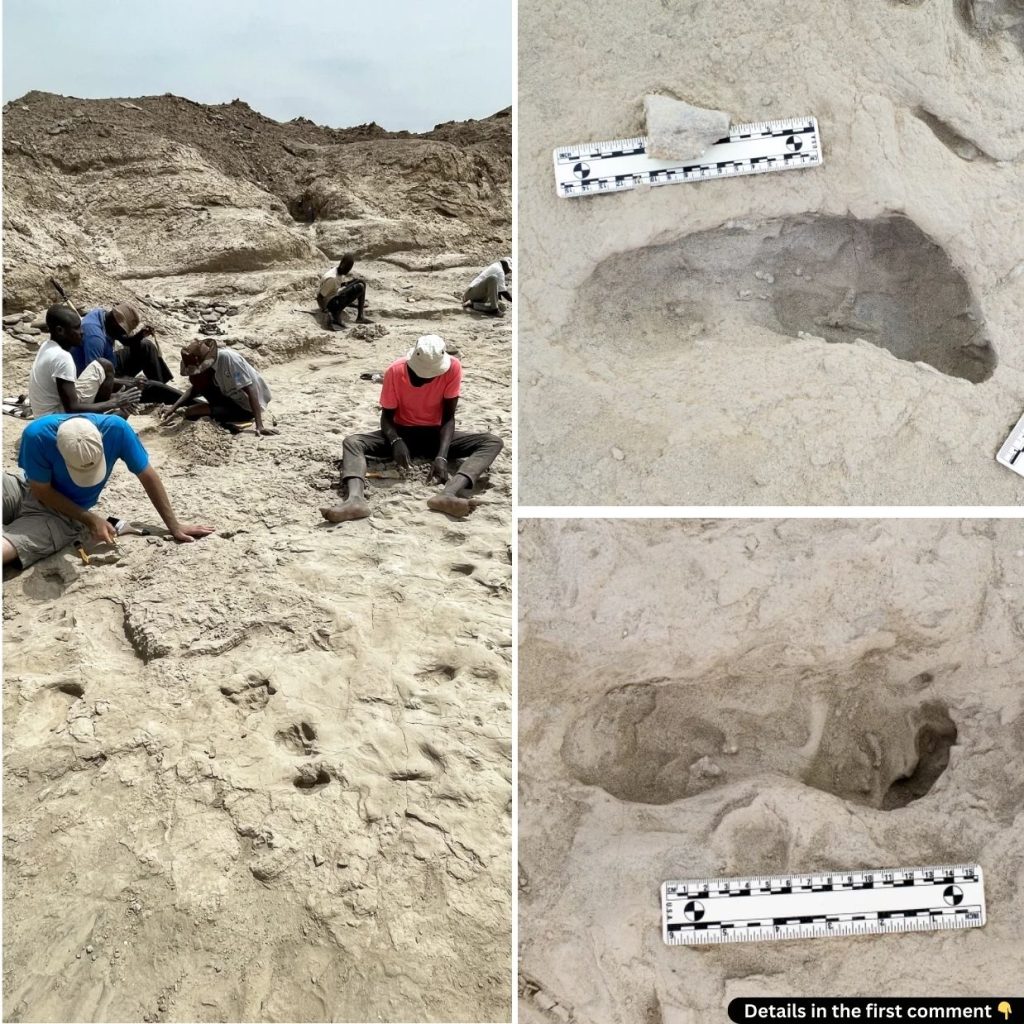

The story begins along the eastern shoreline of Lake Turkana, a location already known for its rich deposits of ancient fossils. In 2021, a single human-like footprint was discovered by a research team exploring the region. At first, the find was thought to be another piece in the puzzle of hominin evolution. However, by 2022, excavation efforts expanded dramatically, revealing a 23-square-meter surface imprinted with 12 footprints in a straight line and three others that veered off in a separate direction. These were not just random impressions left behind in soil. The conditions of the sediment—perfectly balanced between too wet and too dry—allowed these footprints to solidify and survive for over a million years, offering an unusually well-preserved snapshot of life during the Pleistocene.

The longer trail, composed of 12 sequential prints, has been linked to Paranthropus boisei, a species characterized by its large jaws and powerful teeth, adaptations likely developed to process a plant-heavy diet. This hominin was stoutly built and somewhat more specialized in its dietary habits compared to its relatives. In contrast, the three other footprints discovered nearby, which follow a different path, are believed to belong to Homo erectus, one of the most successful and adaptable ancestors of modern humans. Using advanced 3D imaging technology and comparing these prints with those of modern humans walking barefoot, researchers were able to distinguish the differences in stride, foot structure, and gait—clearly identifying two separate hominin species.

What makes this discovery truly captivating is not just the identification of the trackmakers, but the suggestion that they occupied the same space at the same time. The ancient environment of Lake Turkana was no easy place to live. It was a rich and active ecosystem filled with a wide variety of species, from large birds to grazing mammals, and dangerous predators like crocodiles and hippos. Despite the inherent threats of such a setting, both Paranthropus boisei and Homo erectus managed to survive—perhaps even thrive—by developing distinct survival strategies. The evidence of their coexistence suggests they were able to share the landscape and its resources without engaging in direct, destructive competition.

This idea of cohabitation raises profound questions about how early human species interacted with one another. According to Kevin Hatala, the lead researcher on the project, the data shows that these two species may have lived side by side for as long as 100,000 years. This overlap in their timelines hints at the possibility of more than just passive coexistence. Could they have communicated or observed each other? Is it possible they exchanged behaviors or even interbred, in a way reminiscent of the later interactions between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals? Although we don’t yet have direct evidence of such relationships, the fossilized footprints are the closest thing we have to witnessing that prehistoric reality.

Smithsonian anthropologist Briana Pobiner has described the find as “mind-blowing,” emphasizing that it’s like traveling back in time to witness these ancient humans in action. Footprints, she explains, are unlike bones or tools—they are moments frozen in time, capturing a few seconds of life that once passed through a now-barren stretch of earth. Each step preserved in the mud represents a living being with its own purpose, behavior, and possibly even awareness of others in its environment.

The research at Koobi Fora is far from complete. Scientists are hopeful that additional tracks will be found, expanding our understanding of this remarkable time period. The use of cutting-edge tools such as isotopic analysis and genetic testing may eventually help reconstruct the diets, health, and migration patterns of these ancient species in even greater detail. These efforts promise to paint a clearer picture of how early humans lived—and how the evolutionary path that led to us was shaped by such complex, overlapping histories.

What makes the Koobi Fora footprints so significant is their capacity to humanize prehistory. They remind us that human evolution was not a clean, straightforward path from primitive ape to modern man. Instead, it was a tangled, interwoven story of multiple species experimenting with different ways of living and adapting to their environment. The landscape of early humanity was more diverse than previously imagined, filled with different versions of what it meant to be “human,” each leaving behind faint traces of their lives.

As scientific investigation continues in this corner of Kenya, the footprints at Koobi Fora remain a silent but powerful testament to our shared origins. They offer an emotional as well as scientific bridge to our ancestors—living, breathing beings who once walked the same Earth we now inhabit. And in their quiet imprints, we find both questions and answers—reminders of who we were and clues about how we came to be.