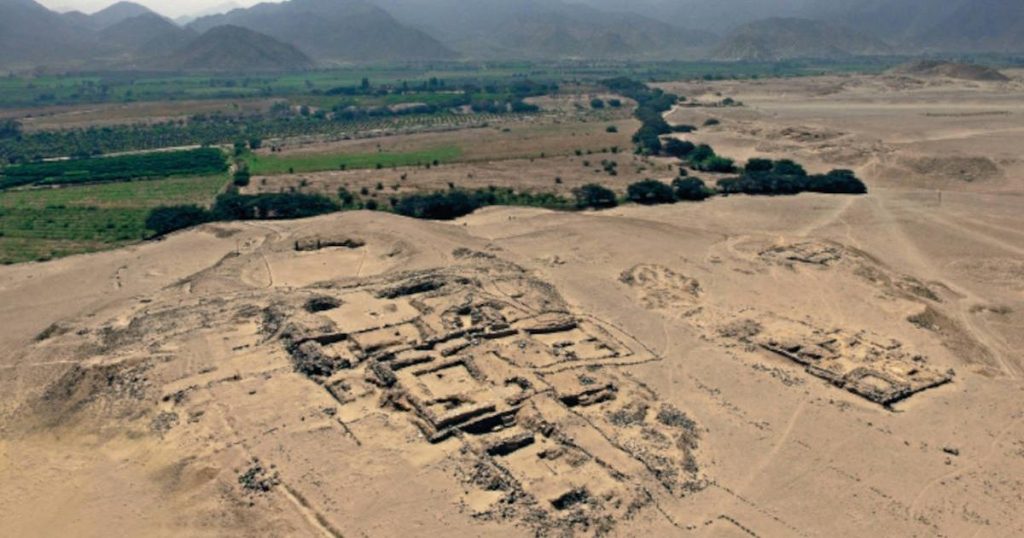

The ancient civilizations of the Americas were far more advanced and industrious than once believed. New archaeological discoveries continue to shed light on the ambitious societies that once thrived there. One of the most remarkable recent finds comes from Peru, near the ancient settlement of Chupacigarro in the central Andes, about 15 miles from the Pacific Ocean. Here, a team of archaeologists has unearthed a previously unknown pyramidal structure, designated Sector F. This location is just under a mile west of the sacred city of Caral, a UNESCO World Heritage site known for its connection to the Norte Chico civilization—the oldest known society in the Americas.

Hidden beneath thick vegetation for millennia, the pyramid remained undetected until recent excavations cleared the dense plant life. Once the vegetation was removed, researchers found a series of stone walls arranged in at least three overlapping platforms. One of the most intriguing aspects of the structure is the presence of large vertical stones called “huancas,” placed prominently at the building’s corners and flanking a central staircase. This staircase likely allowed access to the upper levels, further supporting the idea that the structure had significant ceremonial importance.

Perhaps the most striking discovery at Chupacigarro is a massive geoglyph carved into the landscape. Designed in the profile of a human head, it reflects the artistic style of the Sechín culture, which dates back as far as the fourth millennium BC. This enormous geoglyph measures roughly 204 feet long and 99 feet wide and was created using angular stones carefully arranged in the soil. It is visible from a particular vantage point within the Chupacigarro settlement, suggesting it was deliberately positioned for symbolic or commemorative purposes, likely honoring a notable figure known to the ancient inhabitants.

The significance of the pyramidal structure at Chupacigarro cannot be overstated. Situated near a ravine close to the sacred city of Caral, the newly uncovered site appears to mirror many architectural features found in Caral, including strategic placement on elevated terrain and ceremonial design elements. Dr. Ruth Shady, who leads the excavation team, has announced plans to map the entire area to better understand its scope and relationship to other Norte Chico settlements. The Peruvian government has also expressed interest in incorporating Chupacigarro into the broader tourism experience of Caral, thanks to its structural and cultural parallels.

This pyramid is one of several monuments spread throughout the Supe Valley, a region where the Caral civilization—founded by the Norte Chico culture—flourished between 3000 and 1800 B.C. The area under study at Chupacigarro contains twelve public or ceremonial buildings, arranged on small hills encircling a central plaza within the ravine. The architectural diversity on display, including differences in size, orientation, and design, suggests a complex society capable of coordinating large-scale projects and events. Residential structures have also been found on the outer edges of the site, with smaller buildings positioned around a central feature that includes a sunken circular plaza—a signature design element of the Norte Chico era.

These findings reinforce the belief that a small urban community existed at Chupacigarro as far back as 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, covering an estimated 95 acres. The layout of the site, the public buildings, and the geoglyphs all point to a highly organized culture with religious, political, and commercial dimensions.

The story of Chupacigarro is deeply intertwined with that of Caral, the most famous city built by the Norte Chico people. As the earliest known civilization in the Americas, Caral developed during the same period that ancient societies in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China were forming. Caral served as the cultural and administrative capital, a bustling metropolis during the fourth millennium BC. It featured six massive pyramidal structures, temples, residential zones, circular plazas, an amphitheater, and earthen platform mounds. The architectural sophistication and urban planning of Caral rivaled that of other ancient civilizations across the globe.

Located approximately 200 miles north of Lima along the Pacific coast, the Supe Valley was first studied in 1905 by German archaeologist Max Uhle. However, it wasn’t until the 1970s that researchers began to suspect the mounds in the region were actually pyramids. By the 1990s, full-scale excavations revealed the city of Caral in all its complexity. A major breakthrough occurred in 2000 when radiocarbon dating of reed carrying bags placed Caral’s origins around 3000 B.C., providing strong evidence of an early advanced society in the Americas.

Caral spans about 160 acres and is built on a desert terrace overlooking the fertile Supe River. The city is astonishingly well-preserved, with its pyramids, elite residences, and central plazas showcasing an impressive level of planning. The largest pyramid at Caral rises 60 feet and measures 450 by 500 feet at its base—an area roughly the size of four football fields. A wide staircase leads to an atrium and a sacred altar where offerings were likely burned. The site also includes rooms, courtyards, and three sunken plazas. Housing was arranged by social class, with the elite residing atop pyramids, artisans occupying mid-level residences, and laborers housed in more modest structures on the outskirts.

At its height, Caral is believed to have supported around 3,000 people. Its neighboring settlements, such as Chupacigarro, contributed to a larger population spread across the Supe Valley. Chupacigarro may have functioned as an extension of the main city, serving specialized roles distinct from those in Caral’s urban core.

One of the most compelling theories about Chupacigarro is its role as a commercial or logistical hub. Given its location between the lower Supe Valley and the Huaura Coastline, the site would have been ideally positioned to support trade. Coastal communities could have provided goods such as fish and shellfish, which were not accessible inland. The pyramid at Chupacigarro, notably invisible from the valley below, might have served as a private center for coordinating these exchanges. This implies a high level of planning and suggests that Chupacigarro played a key role in managing the movement of resources between communities.

The discovery of this ancient pyramid at Chupacigarro adds another layer to our understanding of the Norte Chico civilization. It illustrates how early American societies were not only spiritually and culturally rich but also deeply connected through trade and communication. These findings serve as a powerful reminder that the Americas were home to some of the world’s earliest and most sophisticated civilizations, long before the rise of more widely recognized ancient empires. As excavations continue, it is likely that Chupacigarro will yield even more insights into how these ancient peoples lived, worked, and thrived.