A team of underwater archaeologists from the University of Zadar has made a groundbreaking discovery off the coast of Croatia, uncovering a submerged road that dates back to the Neolithic period. This ancient roadway lies beneath five meters of sediment at the submerged archaeological site of Soline, an artificial landmass that once hosted a Neolithic settlement near the island of Korčula.

Korčula is part of an Adriatic archipelago that was originally connected to the mainland. However, due to rising sea levels caused by the melting of the Earth’s ice caps after 12,000 BC, coastal valleys of the Dinaric Mountains began to flood. By approximately 6000 BC, this process had reshaped the landscape, forming the present-day configuration of the archipelago.

The settlement at Soline is attributed to the Hvar culture, also known as the Hvar-Lisičići culture, a Neolithic civilization that flourished along the eastern Adriatic coast. Named after the island of Hvar, this culture played a significant role in prehistoric developments in the region. Previous excavations at Soline have unearthed well-preserved organic materials that have been carbon-dated to roughly 4,900 years ago, offering valuable insights into the daily lives of the people who once inhabited the area.

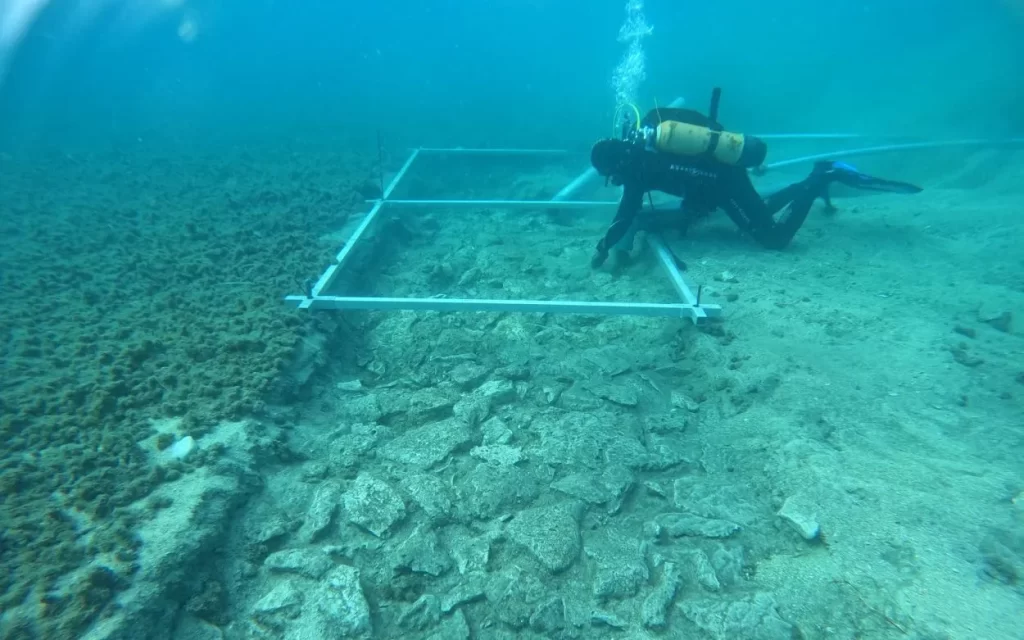

During a recent underwater survey, researchers uncovered a four-meter-wide stone road constructed using precisely laid stone slabs. Based on their analysis, they estimate that this remarkable structure dates back nearly 7,000 years. The discovery of such an engineered feature challenges previous assumptions about the technological capabilities of Neolithic societies in the Adriatic and suggests that the people of the Hvar culture possessed advanced construction skills.

The significance of this find extends beyond Soline. Archaeologists from the University of Zadar have also conducted land surveys on the opposite side of Korčula, specifically in the area of Gradina Bay. During these investigations, Igor Borzić, a researcher from the university’s Archaeology Department, observed unusual formations just beneath the water’s surface. This observation ultimately led to the identification of another submerged settlement, located at a depth of four to five meters.

Similar in layout to Soline, this newly discovered site has yielded an array of artifacts, including stone blades, a stone axe, and fragments of millstones. These artifacts, like those found at Soline, are linked to the Hvar culture, reinforcing the idea that Neolithic settlements in this region were not isolated but part of a broader network of human activity.

The discovery of these submerged settlements sheds light on how Neolithic communities adapted to environmental changes and utilized advanced construction techniques to create pathways and infrastructures that facilitated movement and trade. The road at Soline, in particular, suggests that inhabitants had the knowledge and skills to design and maintain such structures, possibly for accessing other parts of their settlement or for connecting with neighboring communities.

The region surrounding Korčula has long been of interest to archaeologists due to its rich history and abundance of prehistoric remains. However, the recent finds at Soline and Gradina Bay underscore the potential for uncovering even more about the early human occupation of this coastal area. Advances in underwater archaeology have made it possible to explore and document sites that were previously inaccessible, opening new avenues for understanding how ancient civilizations thrived in changing landscapes.

These discoveries contribute significantly to our knowledge of Neolithic societies in the Adriatic. They demonstrate that early human populations in the region were not only adept at building settlements but also capable of constructing sophisticated roads and pathways, which could have served various purposes, including trade, transportation, and ceremonial activities.

Moreover, the presence of well-crafted tools and artifacts at both Soline and Gradina Bay highlights the technological proficiency of the Hvar culture. The stone blades and axes suggest that the inhabitants engaged in activities such as woodworking, agriculture, and food processing, while the millstone fragments indicate a reliance on grain-based diets. These findings provide valuable evidence of how Neolithic communities sustained themselves and interacted with their environment.

The work conducted by the team from the University of Zadar is part of a broader effort to investigate submerged prehistoric landscapes in the Adriatic. As sea levels continue to rise due to contemporary climate change, these ancient underwater sites offer a window into past environmental shifts and how early human societies adapted to them. The findings from Soline and Gradina Bay highlight the resilience and ingenuity of Neolithic communities, who responded to their changing world by developing infrastructure that facilitated their survival.

Future excavations and underwater surveys in the region are expected to yield further insights into these submerged settlements. By employing modern archaeological techniques, including remote sensing and 3D mapping, researchers hope to reconstruct the full extent of these ancient communities and uncover additional evidence of their way of life.

The discoveries at Soline and Gradina Bay are a testament to the enduring human spirit and the ability of early societies to innovate in response to environmental challenges. They remind us that beneath the surface of our oceans and seas, there are still many secrets waiting to be revealed, offering a deeper understanding of our shared past.

With each new discovery, the puzzle of human history becomes more complete, painting a picture of a world where ancient civilizations were far more advanced and interconnected than previously believed. The work of the University of Zadar’s archaeologists is not only rewriting history but also preserving it for future generations to study and appreciate.