The discovery of Queen Nodjmet’s mummy in the Deir el-Bahari Royal Cachette (DB320) remains one of the most fascinating finds in Egyptology. As an ancient Egyptian noblewoman and possibly a queen of the late 20th Dynasty or early 21st Dynasty, Nodjmet was deeply connected to the powerful religious and political landscape of her time. Her carefully preserved remains provide a unique glimpse into the funerary practices and artistry of ancient Egypt.

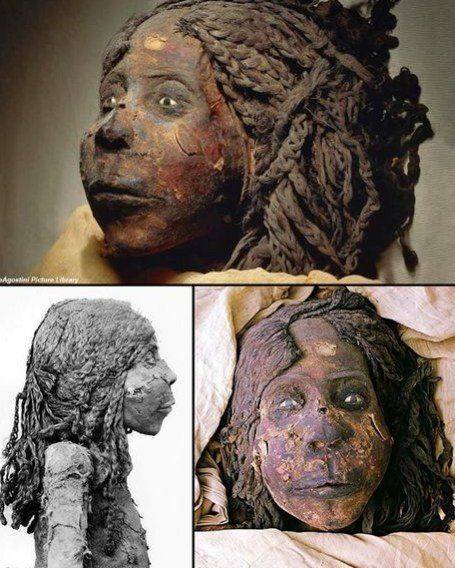

Her mummy was remarkably well-prepared, showcasing the meticulous mummification techniques of the period. One of the most striking features of her preserved body was the use of artificial eyes, crafted from black and white stones, which gave her a more lifelike appearance. This detail highlights the ancient Egyptians’ desire to preserve not only the body but also the dignity and status of the deceased in the afterlife. Her eyebrows were made from real hair, further enhancing the realism of her face. Additionally, she was adorned with a wig, a common practice among Egyptian nobility, symbolizing beauty and status. The embalmers also applied color to her face and body, reinforcing the belief that a well-preserved appearance was essential for the soul’s journey in the afterlife.

Nodjmet was married to Herihor, the influential High Priest of Amun at Thebes, who wielded immense power in Upper Egypt during a time of political transition. While historical records suggest that she may have been a queen, her exact royal status remains debated. Some scholars propose that she was a daughter of Ramesses XI, the last pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty, which would have given her a direct link to the throne. Early in her life, she held prestigious titles such as “Lady of the House” and “Chief of the Harem of Amun,” emphasizing her significant role within the temple and royal court.

Her tomb contained two copies of the Book of the Dead, an essential funerary text that guided the deceased through the afterlife. One of these papyri, identified as EA10490 and now housed in the British Museum, belonged to “the King’s Mother Nodjmet, the daughter of the King’s Mother Hrere.” This inscription suggests a lineage of high-ranking women within the royal and religious hierarchy, further emphasizing the importance of her family.

The second Book of the Dead, also found in her tomb and now cataloged as EA10541 in the British Museum, stands out as one of the most beautifully illustrated papyri from Ancient Egypt. These texts were not just collections of spells; they served as detailed instructions to ensure a smooth passage to the afterlife. The artwork within these manuscripts reveals the high level of craftsmanship and artistic expression of the time.

The discovery of Nodjmet’s mummy, along with these significant artifacts, sheds light on the evolving religious and funerary practices during the transition from the 20th to the 21st Dynasty. This period was marked by the decline of centralized pharaonic power and the rising influence of the priesthood, particularly in Thebes. Herihor, Nodjmet’s husband, was not only the High Priest of Amun but also took on titles and powers traditionally reserved for the pharaoh, reflecting a shift in governance where religious leaders held considerable political authority.

The inclusion of two Books of the Dead in her burial suggests that Nodjmet was highly regarded and that her journey to the afterlife was of great concern to those who prepared her tomb. These texts contained spells to protect her, guide her through the trials of the underworld, and ensure she reached the Field of Reeds, the Egyptian equivalent of paradise. The illustrations within these papyri depict various deities, ritual scenes, and symbolic elements essential for understanding ancient Egyptian religious beliefs.

Her mummification itself indicates that she was treated with the highest level of care. The application of artificial eyes, real hair, and painted skin points to the belief that maintaining one’s physical identity in the afterlife was crucial. The use of wigs was particularly important, as they were symbols of beauty, social standing, and divine connection. Nobles and royalty often wore elaborate wigs in life, and this practice extended into death to ensure that they maintained their regal appearance in eternity.

The Deir el-Bahari Royal Cachette, where Nodjmet’s mummy was found, was a hidden burial site that contained the remains of numerous pharaohs and high-ranking individuals. This cache was created by Egyptian priests during the Third Intermediate Period as a means of protecting royal mummies from tomb robbers. Many of these mummies had originally been interred in grand tombs in the Valley of the Kings but were later relocated to safer locations. The discovery of this cache in the 19th century provided Egyptologists with invaluable insights into the burial customs and preservation techniques of the time.

Nodjmet’s burial, along with the presence of her papyri and other artifacts, underscores her significant standing within the elite circles of ancient Egypt. While the details of her life remain partially obscured by time, her well-preserved remains and the richness of her funerary texts allow historians to piece together aspects of her story. She lived in an era of change, where the traditional rule of the pharaohs was being challenged by powerful religious institutions. Her husband, Herihor, exemplifies this shift, as he assumed titles that blurred the lines between religious and royal authority.

The study of Nodjmet’s mummy and her Books of the Dead continues to provide scholars with crucial information about the intersection of religion, politics, and art in ancient Egypt. The exquisite illustrations in her funerary texts reveal not only theological concepts but also the craftsmanship and cultural sophistication of her time. Her burial site, hidden away to preserve the dignity of the deceased against the threat of looters, reflects the challenges faced by Egyptian elites during periods of instability.

In the grand narrative of Egyptian history, Queen Nodjmet’s mummy represents more than just a well-preserved body; it is a testament to the enduring power of Egyptian religious beliefs and artistic traditions. Her artificial eyes, delicate hair placement, and painted features remind us of the lengths to which the ancient Egyptians went to honor and preserve their dead. The discovery of her papyri further cements her status as a key figure in understanding the spiritual and ritualistic practices of her time.

Ultimately, Queen Nodjmet’s legacy endures not just through her titles or her connection to powerful figures, but through the artistic and religious treasures that accompanied her into the afterlife. Her story, preserved within the pages of the Book of the Dead, continues to captivate historians and enthusiasts alike, offering an intimate look at the beliefs and customs that defined one of the most fascinating civilizations in history.